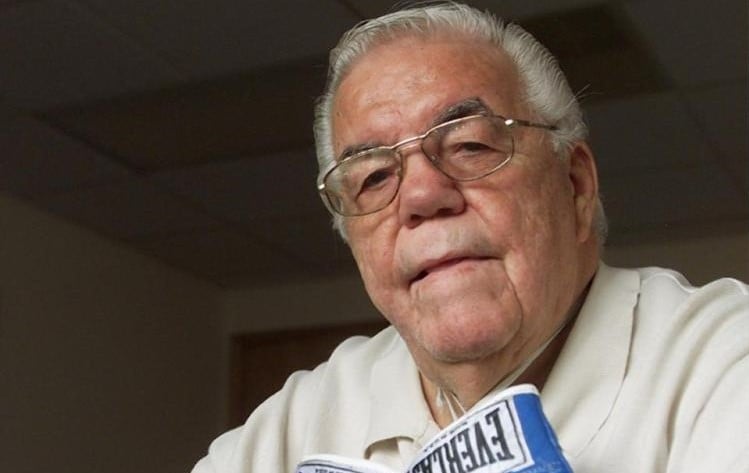

Lou Duva passes away

From his first breath until his last, a little less than three months short of his 95th birthday, Lou Duva was a fighter. The drive, hard work and hustle that powered him through a hardscrabble childhood helped him produce a life in boxing that touched seven decades and saw him inducted into several halls of fame, including the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1998. He experienced boxing from multiple perspectives – boxer, trainer, manager and promoter – and he approached every task with a fiery passion that resulted in extraordinary success but also occasionally boiled over and pushed his health toward the breaking point.

“I don’t know of anybody else who fights for his fighters like I do,” Duva told “In This Corner” author Dave Anderson. “I don’t mean pretending to fight, that’s bull***t. I mean ready to fight. I’m always fighting for my fighters.”

Duva’s own fight with the game of life ended Wednesday at St. Joseph Hospital in Paterson, New Jersey, where he was reportedly admitted nine days ago. By all measures, he emerged a winner and a champion.

Born the fifth of seven children to Italian immigrants Salvatore and Saveria on May 28, 1922 in Manhattan, Duva and his family settled in Paterson when Lou was four years old. To help make ends meet, Duva caddied at the local golf course, delivered newspapers, shined shoes and set up pins at the bowling alley.

“I knew I had to scrap for everything I’d ever want in life,” Duva said in his 2016 autobiography “A Fighting Life: My Seven Decades in Boxing.” “Looking back, I wouldn’t have had it any other way. Fighting my way through life has made it an interesting, fun ride – bumps and bruises included.”

He gravitated toward boxing through his older brother Carl, who, according to BoxRec, went 18-6-3 (with 5 knockouts) in a 10-year career that ended in 1940. Starting at age 10, Duva tagged along. Four years later, Carl showed Lou how to box. Duva also absorbed knowledge by attending Doc Bier’s training camp at Pompton Lakes and watching Joe Louis and his trainer Jack Blackburn.

To bring even more money to the family coffers, Duva joined the Civilian Conservation Corps at age 16, by doctoring an 18-year-old friend’s birth certificate. There, he learned various office skills, as well as drive trucks (both of which would serve him well in the future), and he also scratched his boxing itch by taking part in “smokers” for between $5 and $12 per fight, based on the level of competition. Once he left the CCC in 1940, Duva began boxing as an amateur and, later that year, won the New Jersey Diamond Belt tournament as a welterweight. His amateur career was cut short when Duva joined the U.S. Army following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Though he was listed as a “tank destroyer driver,” most of his time at Fort Hood, Texas, was spent on KP duty, driving garbage trucks and, more pleasingly, serving as the boxing instructor.

Following his three-year Army stint, Duva continued to hustle. He was a truck driver for H.W. Mills for four years, then purchased his own truck and went into business for himself, expanding his fleet to 32 trucks before selling the company. According to BoxRec, Duva was 6-10-1 with no knockouts between June 1942 and July 1945 but Duva said in his autobiography he would have been a better fighter had he been able to devote himself entirely to training instead of juggling time between the trucking company (then a bail bonds business), tending to his growing family and helping his brother Carl run his gym in Paterson. At that gym, the seeds of Duva’s future sprouted as he worked with top fighters like Fitzie Pruden and Lee Savold. Also, thanks to his many trips between Paterson and the garment district in New York City, Duva was able to visit Stillman’s Gym regularly and pick up more valuable knowledge. Duva went on to purchase his own gym in Paterson and used his income from his other jobs to keep it afloat.

The connections he formed through the years enabled him to put together the fight card topped by Joey Giardello’s attempt to win Dick Tiger’s middleweight title in Atlantic City in December 1963. In what was considered an upset, Giardello out-pointed Tiger over 15 rounds and, just like that, Duva had his first world champion. Giardello out-pointed Rubin Carter to retain the title but lost it back to Tiger on points two fights later. That experience gave Duva a taste of big-time boxing and he liked it enough to continue dreaming big. The building blocks to those dreams, however, still needed to be assembled.

Starting in 1977, Duva and his family formed Main Events and began promoting regular shows at Ice World in Totowa, New Jersey. This was an old-fashioned “up-from-the-bootstraps” grassroots operation with a built-in labor force; his children helped with matchmaking, bookkeeping, ticket-selling and other sundry tasks. Son Dan, now a lawyer, closed deals by the dozen, including the closed-circuit TV rights to the first Roberto Duran-Sugar Ray Leonard fight. But it was another fight involving Leonard – his first fight with Thomas Hearns – that vaulted Main Events into the upper reaches of the sport.

Dan Duva and Shelly Finkel (who later co-managed Pernell Whitaker, Meldrick Taylor and Mark Breland with Duva) helped Main Events land the promotional rights to Leonard-Hearns I . They raised the $13 million necessary to stage the match, which was beamed to 275 closed-circuit locations and was the first championship fight to be made available on pay-per-view within homes.

The success of promoting Leonard-Hearns I sent a powerful message to the boxing industry: There was a viable alternative for boxers who didn’t want to sign with Don King or Bob Arum. To that point, Duva’s only world champion had been Giardello but, in the intervening years, he worked with 18 more. That roll call included Hall-of-Famers Arturo Gatti, Lennox Lewis, Mike McCallum and Hector Camacho, as well as Michael Moorer, Livingstone Bramble, Johnny Bumphus, Rocky Lockridge, Tony Tucker, Darrin Van Horn, John-John Molina, Eddie Hopson, Vinny Pazienza, Bobby Czyz and Fernando Vargas but his most celebrated assemblage of talent was achieved following the 1984 Olympics when Main Events signed American gold medalists Whitaker, Breland, Taylor and Tyrell Biggs, as well as bronze medalist Evander Holyfield. All were guided to title shots and, with the exception of Biggs, who had the misfortune of challenging a prime Mike Tyson, all became champions. Better yet, Whitaker joined Duva in Canastota and, in June, Holyfield will do so as well.

Duva and fellow Hall-of-Famer George Benton formed one of history’s most prolific corner partnerships; Benton was the soft-spoken strategist, while Duva was the boisterous cheerleader/cutman who amplified Benton’s in-ring smarts with his own considerable bag of tricks. For most of the 1980s and 1990s, they were an almost constant presence on American TV screens and those screens chronicled the good – and the not-so-good.

Though he was best known as a master motivator, who repeatedly told his charges, “You’re boxing beautiful,” the street-smart Duva also seized on every edge. One of the most notable examples of Duva’s savvy took place May 18, 1986 in Providence, R.I. when Bumphus fought Marlon Starling for “Moochie’s” USBA welterweight title.

An accidental butt near the end of round six opened a severe gash on Bumphus’ forehead. Duva alerted the ring physician and talked him into looking at the cut. After doing so, the fight was stopped. But while referee Vinny Rainone and the commissioners sorted out the ruling, Duva ordered his cutman to “Don’t work on a Goddamn thing” and he even widened the untreated slice slightly with his fingers while showing it to Starling and his team.

This seemingly counterintuitive action was influenced by two factors; first, with the judges’ scores being announced over the loudspeaker after every round as part of an open-scoring experiment, Duva knew his fighter was ahead (the scores were 60-54, 59-56 and 59-55) and, second, he knew that under the USBA “six-round” rule (which was explained to Duva in the dressing room before the bout), his fighter would win by technical decision if the fight were stopped at that point. It was and Bumphus won the belt on Starling’s home turf.

NFL Hall-of-Famer Weeb Eubank once said, “All I want is my fair advantage,” and this incident proves Duva, as a cornerman, ascribed to the same philosophy.

On a more lighthearted note, Duva convinced Bramble’s basketball coach, who came to see his onetime charge challenge WBA lightweight champion Ray Mancini in June 1984, to pose as Bramble’s witch doctor at the press conference in order to rattle “Boom Boom’s” cage.

“We told him not to speak but rather to just walk into the room and sit down near the front so that Mancini and his people could see him,” Duva said in his autobiography. “I gave the coach/voodoo doctor a big book. He would look down at the book and point over at Mancini. Dave Wolf, Mancini’s manager, was going crazy with this guy reciting stuff and pointing at Mancini. It was working like a charm.

“‘What’s he doing? What’s he doing?’ Wolf was screaming. ‘Shush! Be quiet. He’s practicing his religion,’ I said. You could say it worked because Bramble knocked Mancini out for the victory.”

But if Duva felt his fighter was being treated unfairly, he not only complained to the officials but he also was willing to take matters into his own hands – literally.

Perhaps the most infamous example of Duva’s pugnacity took place in the moments after Pazienza lost his title challenge to WBC super welterweight king Roger Mayweather. Incensed by what he saw as Mayweather’s repeated fouls, Duva charged into the ring after the final bell and emerged with a cut on his cheek.

“The thing with Mayweather was, he was hitting Vinny Pazienza after the bell,” Duva told Anderson. “He done it four times. I know Vinny’s temperament. He’s coming back to the corner muttering, ‘I’ll kill this sonofabitch.’ Now the last round ends and the referee (Mills Lane) goes over and breaks ’em up. While he does that, I’m thinking, Vinny’s going to go after him. While I’m hurrying up the stairs and through the ropes, you can look at the tape, you see Vinny swerve off and Mayweather swerve off. Just as I get there, Mayweather looks at me and says, ‘What are you going to do about it? I beat your man.’ I said, ‘You got to be a jerk-off. You hit him after the bell four times. The referee never done nothing about it.’

“As we’re arguing and cursing, a 330-pound security guard grabs me. As he does that, he trips. I go down with him. And when I go down with him, boom, he pops me in the eye. When I get up, I’m so mad, I’m going after Mayweather and now everybody grabs me. Some people thought I threw punches at the referee Mills Lane but Mills said, ‘Lou never threw a punch at me.’ I never even threw a punch at Mayweather, never. Cursed at him, went after him, yes, I did do that. Now the Nevada commission wants to follow it up because the television people played it up big; the newspapers played it up big. The windup is, they’re going to suspend me; they’re going to take my license away. But in the hearing, we slowed down the tape. They said, ‘Look, just apologize and we’ll fine you $750. You’re bailed out. We’re bailed out.’ That’s what we did.”

His frequent outbursts may have gotten him into trouble with boxing authorities but they also paid him dividends beyond the squared circle. Thanks to a friendship with wrestling manager Captain Lou Albano that was formed when Duva staged wrestling shows at Ice World, Duva was included in a boxing-themed WrestleMania 2 story line involving Mr. T and “Rowdy” Roddy Piper. Duva, who played the role of Piper’s trainer, was a perfect fit for the theatrics of “sports entertainment” and, after Piper lost the match by disqualification by body-slamming Mr. T, Duva seemed right at home during the subsequent melee.

A decade later, the 74-year-old Duva was caught up in a far more serious – and totally unscripted – riot in Madison Square Garden when his fighter, Andrew Golota, was disqualified for hitting Riddick Bowe with multiple low blows. Bowe’s enraged entourage charged into the ring and Duva, along with others, tried to protect Golota. Due to his history of heart problems, doctors had implanted a defibrillator in Duva’s chest and the stress caused the device to send a jolt of electricity that caused Duva to fall to the canvas. Medical personnel immediately pulled Duva out of the ring, strapped him onto a stretcher and carried him out of the still-raging arena into his dressing room, where he was given oxygen. Duva trained Golota for his rematch with Bowe (which also ended in a DQ loss) and his failed title challenge against Lennox Lewis but “The Foul Pole” was eventually given over to Roger Bloodworth.

For all the scuffles and disappointments, his greatest moment of triumph happened moments after Holyfield scored a one-punch knockout of Buster Douglas to win the undisputed heavyweight championship in October 1990. Years earlier, he and former heavyweight champion Rocky Marciano (one of Duva’s best friends) hatched a project to turn six NFL players into heavyweight prospects but Marciano’s death following a plane crash in 1969 caused that plan to die with it. But Duva continued to work toward that dream and Holyfield’s victory 21 years later was the fulfillment of that vision. The 68-year-old Duva reportedly bounded toward a corner, pointed to the sky and bellowed, “We did it Rocky! We did it!”

In 1996, the 44-year-old Dan Duva died from a brain tumor and, in December 1999, Dino and Donna Duva filed suit, claiming Dan’s widow Kathy and a lawyer had taken control of Main Events. Kathy’s legal team replied that Dan had been vital to Main Events’ good fortune and that he had left the company to Kathy and her children. A sealed settlement was reached; Kathy Duva retained Main Events, while Lou launched Duva Boxing in January 2000. Donna left the company following Oscar Diaz’s career-ending loss to Delvin Rodriguez in 2008 and Duva Boxing officially shut down in 2010.

Besides the IBHOF, Duva was inducted into the New Jersey Boxing Hall of Fame, the National Italian-American Sports Hall of Fame and the Meadowlands Sports Hall of Fame. He was named Manager of the Year by the Boxing Writers Association of America in 1984 and 1993 (he shared the latter honor with Finkel) and the organization also bestowed him the James J. Walker award for Long and Meritorious Service to Boxing in 1993.

In later years, Duva regularly attended the IBHOF’s induction weekend and his blend of charisma, vivid storytelling and biting humor proved highly popular.

Duva was once quoted as saying, “When it’s time to go, I’ll probably be fighting to get out of the casket. I’ll be yelling at the priest instead of a referee.”

Once a fighter, always a fighter.

*

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, West Virginia. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 15 writing awards, including 12 in the last seven years and two first-place awards since 2011. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. He is the author of “Tales from the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics.” To order, please visit Amazon.com. To contact Groves, use the email [email protected].

Struggling to locate a copy of THE RING magazine? Try here or…

SUBSCRIBE

You can subscribe to the print and digital editions of THE RING magazine by clicking the banner or here. You can also order the current issue, which is on newsstands, or back issues from our subscribe page. On the cover this month: THE RING reveals The Greatest Heavyweight of All Time.