Hands of Stone: 10 fights that cemented Duran’s legend – part II

Part two of “10 fights that cemented Roberto Duran’s legend,” compiled by RingTV.com’s resident historian Lee Groves, chronicles five of Hands of Stone’s greatest victories, spanning 15 years – from Duran’s pound-for-pound prime to his time as a middle-aged underdog title challenger.

5. March 16, 1974 – KO 11 Esteban DeJesus II, Gimnasio Nuevo Panama, Panama City, Panama

During his six-year career, Duran had achieved just about everything a fighter could want. First of all, he was a world champion and he was earning purses commensurate with that standing. Second, he enjoyed worldwide sporting fame and that status gained him entry to events that otherwise would have shut him out. Finally, he had that enviable blend that all sportsmen seek: The youth and energy to command his body to do his mind’s bidding and the experience to know exactly what he should tell his body to do.

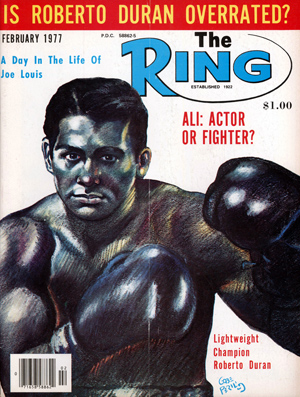

Although he shared a version of the lightweight championship with power-punching Mexican Rodolfo Gonzalez, Duran was considered the premier 135-pounder in the world. Moreover, at age 22, some observers were already saying Duran had the potential to topple Benny Leonard as the greatest lightweight ever to walk the earth.

But for all the accolades and honors, Duran’s life still wasn’t complete. Despite notching three successful defenses since dethroning Buchanan and amassing a sterling 41-1 (35) record, the “1” in the loss column ate at him. On Dec. 17, 1972 an unknown upstart named Esteban DeJesus decisively out-pointed Duran in a non-title fight. Not only that, the slick boxing Puerto Rican dropped Duran for a six-count with a hook in round one. Duran tried to make up ground for the rest of the fight but DeJesus refused to let him.

But for all the accolades and honors, Duran’s life still wasn’t complete. Despite notching three successful defenses since dethroning Buchanan and amassing a sterling 41-1 (35) record, the “1” in the loss column ate at him. On Dec. 17, 1972 an unknown upstart named Esteban DeJesus decisively out-pointed Duran in a non-title fight. Not only that, the slick boxing Puerto Rican dropped Duran for a six-count with a hook in round one. Duran tried to make up ground for the rest of the fight but DeJesus refused to let him.

Duran knew he wasn’t at his best coming into that fight. Two months earlier he had been involved in a car accident that resulted in an elbow injury and several facial lacerations. But Duran also was gripped by complacency; he simply didn’t believe DeJesus was good enough to beat him. The judges saw it differently, as DeJesus won 6-2-2, 6-3-1 and 5-4.

Since then Duran had gone 10-0 (8) while DeJesus had won eight straight with three knockouts. DeJesus’ victims included Ray Lampkin (twice), Johnny Gant and former champion Alfonzo “Peppermint” Frazier, meaning Duran had not lost to a one-hit wonder.

Duran entered the fight a 2-to-1 favorite but less than 90 seconds into the fight the Puerto Rican challenger caused lightning to strike twice as a blistering hook to the point of the chin dropped Duran for the second consecutive meeting. Duran’s partisans jumped out of their seats as they called for their hero to get up, but they need not have worried, for Duran arose and exchanged blows as if nothing had happened.

The third round was particularly torrid as the two lightweights swapped punches at an amazing pace. They whipped dozens of power shots at one another and the crowd did their best to yelp in time with each of Duran’s blockbusters. By the middle rounds Duran had cemented his dominance, not only because of his incredible pressure but also due to the scorching Panamanian heat. According to ABC’s Howard Cosell, the temperature was in the mid-90s and the humidity made the site feel like a “steam bath.”

A five-punch combination highlighted by a hook to the body and a right to the temple caused DeJesus to sink to the floor in the final minute of the seventh. Duran smartly moved inside and pounded DeJesus’ ribs in the eighth, during which an up-and-down combination nearly floored the challenger. Duran now was landing a prohibitively high percentage of his power punches and the effects were etched in DeJesus’ face, body and behavior. His fighter’s heart commanded him to soldier on and he did the best he could under the circumstances. But his body could muster only so much energy and resistance and eventually DeJesus reached his limit.

DeJesus tried to keep his distance early in the 11th but Duran closed the gap, then closed the show. A five-punch volley that included a hook to the body and a final right to the head decked DeJesus for the second time. Without the energy or the will to go on, DeJesus began to rise only after referee Isaac Herrera tolled the final 10.

Not only did Duran secure his vengeance, he evened the score in terms of knockdowns suffered at two apiece. As recounted earlier, Duran won the rubber match by 12th-round KO but their bitter feud really ended when the 37-year-old DeJesus, his body ravaged with AIDS, was near death. Hearing about DeJesus’ plight, Duran flew to DeJesus’ bedside in Puerto Rico and despite the fears of the time Duran hugged, kissed and embraced his rival without any regard to his own potential infection. His gesture won him the respect, admiration and love of Puerto Ricans, who previously had good reason to disparage Duran because of his frequent and ceaseless barbs. By showing his true self, Duran righted long-established wrongs.

4. Jan. 29, 1983 – KO 4 Pipino Cuevas, Sports Arena, Los Angeles, California

As Duran began his 16th year as a professional, the sight of the primal beast that laid waste to the lightweight division seemed a distant memory. The scourge of “No Mas” inflicted untold damage to his reputation and Duran’s personal pain extended to his ring performances. Even when he won it was obvious something was missing. Was  it age? Was it motivation? Was it angst? Or was it something that no one else knew? This war was Duran’s to wage and if his 1982 campaign was any indicator he was losing it.

it age? Was it motivation? Was it angst? Or was it something that no one else knew? This war was Duran’s to wage and if his 1982 campaign was any indicator he was losing it.

In January, WBC junior middleweight titlist Wilfred Benitez comprehensively out-boxed Duran in winning a unanimous decision that was nowhere near as close as the scorecards indicated (143-142, 144-141 and 145-141). Then on Sept. 4, with a potential showdown with Tony Ayala Jr. on the horizon, a blubbery and listless Duran lost to former sparring partner Kirkland Laing on a 10-round split decision that should have been unanimous. The final indignity took place on Nov. 12 when a flabby Duran, weighing a career-high 157 and making a paltry $25,000 pay check, sleep-walked through a 10-round win over Jimmy Batten. At Duran’s insistence, the Batten bout served as the walk-out bout for the classic first bout between Aaron Pryor and Alexis Arguello.

It was a sad illustration of just how far Duran had fallen. The man who was used to creating history was relegated to an afterthought at the site of history.

Duran seemed lost. His legendary trainers Ray Arcel and Freddie Brown left Duran after “No Mas” and promoter Don King followed after the Laing disaster. Duran turned to King’s rival Bob Arum to continue his career and at first Arum was reluctant. But before making the final decision to reject Duran Arum sought advice from Teddy Brenner, regarded by many as the greatest matchmaker boxing has ever known.

“There’s nothing wrong with this guy, physically,” Brenner told Steve Farhood in the November 1983 issue of KO.  “He’s never taken a beating. Whether or not he wants to fight again is a question mark. King chased him. Duran was waiting for one kind word. He came to us, we sat him down. We gave him a chance. If we hadn’t, it might have been the end for him.”

“He’s never taken a beating. Whether or not he wants to fight again is a question mark. King chased him. Duran was waiting for one kind word. He came to us, we sat him down. We gave him a chance. If we hadn’t, it might have been the end for him.”

Brenner’s word was enough for Arum to pull the trigger and sign Duran.

“I don’t know about boxing, but I’ve got a man who knows as much about fighters as anybody, and Teddy said there was nothing wrong with Duran that being in good physical and mental condition wouldn’t solve,” Arum said at the time. “Teddy said that if you get him mentally right, he’d probably beat anybody around.”

Duran’s first fight under Arum was the 10-rounder against Batten and while Duran won the optics weren’t encouraging. So in a last-ditch move to save Duran’s career, Top Rank arranged a fight between Duran and former WBA welterweight king Pipino Cuevas in January 1983. It was a critical fight for both men, for if Cuevas won, he’d be in line to fight Donald Curry for Curry’s WBA 147-pound crown, but if Duran prevailed he’d get a crack at WBA junior middleweight king Davey Moore.

Four years earlier it would have been a sensational multi-million dollar match but even now it was a marquee attraction. Cuevas was a bomb-throwing monster whose left hooks shattered speed bags and opponents’ jaws but he too had fallen on hard times. After Thomas Hearns ended his four-year WBA welterweight championship reign with an emasculating second round TKO, Cuevas scored two early knockouts of Bernardo Prada and Jorgen  Hansen but in his most recent fight he lost a 10 round decision to previously unknown Roger Stafford, a result so shocking that it was deemed THE RING’s 1981 Upset of the Year.

Hansen but in his most recent fight he lost a 10 round decision to previously unknown Roger Stafford, a result so shocking that it was deemed THE RING’s 1981 Upset of the Year.

Critics may have called Duran-Cuevas a battle of tarnished legends but the fans that packed the Sports Arena placed more regard on the word “legends” than the word “tarnished” and eagerly awaited the fireworks they knew were coming.

With potential redemption just around the corner, both men whipped themselves into fantastic condition. Cuevas, who never entered a ring in less than top shape, weighed 149 while Duran surprised many by scaling a hard, trim 152, his lightest weight since the “No Mas” fight. The number on the scale opened some eyes but those who owned the more jaded ones knew that weight alone wasn’t a reliable indicator of future performance. To them, Duran passed the first test by reporting in excellent shape but to convince them he had to get past Cuevas, and do so impressively.

It was Cuevas, however, that had the best of things in the first round. He landed several of his trademark hooks against Duran’s rock-solid jaw and his newly toned body and the heavily Mexican crowd whooped in delight. But Duran turned the fight in round two by going toe-to-toe with the heavier punching Cuevas. For the first time since his magical night in Montreal against Sugar Ray Leonard, Duran was sharp, quick and menacing as he whipped in combinations and defiantly walked through Cuevas’ best bombs.

his magical night in Montreal against Sugar Ray Leonard, Duran was sharp, quick and menacing as he whipped in combinations and defiantly walked through Cuevas’ best bombs.

As the fight neared the midway point of round four Duran was in control, though Cuevas’ fists presented a constant threat. Duran’s deft feinting finally produced an opening for a devastating lead right that turned Cuevas’ legs to jelly. A follow-up flurry capped by a right uppercut-left uppercut sent Cuevas reeling into the corner pad for a “but-for-the-ropes” knockdown.

After referee James Jen-Kin finished the mandatory eight count Duran trapped Cuevas on the ropes and let both fists fly. The Mexican tried to fight back but Duran proved to be too much. A huge right hand to the jaw was followed by a final flurry of body shots that caused Cuevas to slump to the canvas. Jen-Kin saw all he needed to see and stopped the fight with Cuevas still on all fours.

Observers were left to shake their heads in wonder. “How could this be the same man who looked so horrible against Laing?” they thought. “But now we can’t wait to see him against Davey Moore.”

Neither could Duran.

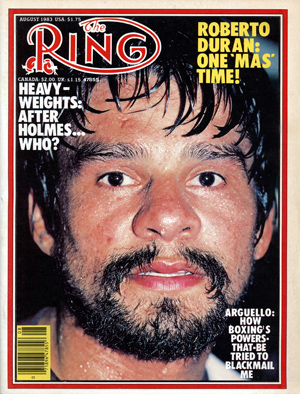

3. Feb. 24, 1989 – W 12 Iran Barkley, Convention Center, Atlantic City, New Jersey

Every once in a great while, a fighter comes along who is capable of creating magic. Muhammad Ali was one such athlete, for he sprung historic upsets of Sonny Liston and George Foreman because he lived to prove “the experts” wrong. Bernard Hopkins is another, for he was left for dead before his fights with Felix Trinidad, Antonio Tarver and Kelly Pavlik before shocking the world with decisive victories over each. As he approaches his 49th birthday, “The Executioner’s” sorcery continues to amaze.

Duran, of course, also should be counted among boxing’s greatest wizards. Thirteen years of nearly uninterrupted success was followed by eight-plus years of dizzying peaks, humbling valleys and stretches of mediocrity – at least when compared to his previous standard. Time after time, Duran shook off the disappointments by taking a long break, then starting over. Such was the case after the “No Mas” fight in November 1980 (nine months), the KO loss to Thomas Hearns (19 months) and a bitter split-decision loss to Robbie Sims (11 months). Each time Duran brushed himself off and began a new winning streak that eventually led to big-money opportunities.

Since the loss to Sims, Duran’s sixth in his last 18 fights since the Leonard rematch, Duran had run off five straight wins against decent opposition but hardly looked like a world-beater in any of them. Nevertheless, Duran’s name still had massive box-office appeal and at age 37, the 21-year ring veteran didn’t appear to be a mortal threat to a champion’s crown.

That low-risk, high-reward formula certainly appealed to Iran Barkley, whose out-of-left field overhand right separated Thomas Hearns from his WBC middleweight title the previous June. The three round knockout was deemed THE RING’s 1988 Upset of the Year and “The Blade’s” brain trust believed Duran to be a lucrative yet do-able first-defense assignment.

That low-risk, high-reward formula certainly appealed to Iran Barkley, whose out-of-left field overhand right separated Thomas Hearns from his WBC middleweight title the previous June. The three round knockout was deemed THE RING’s 1988 Upset of the Year and “The Blade’s” brain trust believed Duran to be a lucrative yet do-able first-defense assignment.

But Barkley’s desire to fight Duran wasn’t just about making “easy” money; his motivation was also deeply personal. Davey Moore, the man Duran brutally dethroned six years earlier, was a close friend of Barkley’s and he felt, quite rightly, that the beating Duran dished out effectively ruined the rest of Moore’s life. That life was unexpectedly snuffed out in June 1988 when the 28-year-old Moore’s parked car slipped out of gear and ran over him. Barkley dedicated the Duran fight to Moore’s memory and vowed to gain indirect vengeance for what he felt was a great wrong.

The 6-foot-1 Barkley was an imposing physical specimen. Standing six-and-a-half inches taller and sporting a five-and-a-half edge in reach, the 28-year-old Barkley also was nine years younger and wielded a potent left hook that was responsible for most of the 16 knockouts in his 25-4 record.

The 6-foot-1 Barkley was an imposing physical specimen. Standing six-and-a-half inches taller and sporting a five-and-a-half edge in reach, the 28-year-old Barkley also was nine years younger and wielded a potent left hook that was responsible for most of the 16 knockouts in his 25-4 record.

This Bronx Bomber was also a survivor, both in and out of the ring. The onetime member of the street gang “The Black Spades,” Barkley turned to boxing and used a powerful but often crude style to bulldoze opponents. He overcame three early losses to put together a 13-fight win streak that earned him a shot at the vacant WBA middleweight title against Sumbu Kalambay. After losing a 15-round decision, Barkley scored two knockout wins – including a sensational off-the-floor fifth round stoppage of Michael Olajide – to secure the fight with Hearns. Just five days after the death of Moore, Barkley overcame two horribly cut eyes to stop “The Hit Man” in scintillating fashion.

Despite his emotional declarations, Barkley opened the bout by calmly working behind the jab, utilizing an unusually tight guard and firing straighter-than-usual power shots.

Duran, for his part, circled the stalking Barkley and looked for chances to slip in his trademark counter rights. Barkley appeared to control the vast majority of the opening round but Duran erased all his solid work by slipping Barkley’s jab and firing a well-timed right to the ear that badly wobbled the champion. Any doubts about Duran’s power at 160 – at least on this night – were erased by that single blow and Duran would put that information to good use later in the bout.

Barkley’s constant punching and heavy body shots trumped Duran’s flashy replies in rounds two through six but Duran picked up his pace considerably in the seventh. With 1:21 remaining in that stanza, Duran nailed Barkley with a right over the top that wobbled his legs. Barkley answered with a flush double hook that would have laid out most middleweights but Duran’s legendary chin absorbed them with nary a flinch.

Barkley’s constant punching and heavy body shots trumped Duran’s flashy replies in rounds two through six but Duran picked up his pace considerably in the seventh. With 1:21 remaining in that stanza, Duran nailed Barkley with a right over the top that wobbled his legs. Barkley answered with a flush double hook that would have laid out most middleweights but Duran’s legendary chin absorbed them with nary a flinch.

That chin was tested again early in the eighth when a Barkley hook spun Duran nearly 180 degrees but, as Barkley had done previously, Duran bounced back with plenty of his own offense. His peppery combinations out-shined Barkley’s bombs in rounds eight, nine and 10, and his accurate rights swelled, cut and nearly closed the champion’s left eye.

Surprisingly, it was the younger Barkley who was breathing heavily in his corner between rounds 10 and 11 while the bright-eyed Duran remained remarkably fresh. As he pondered his situation, Duran’s eyes revealed much about his state of mind. In his youth they had the look of a frothing assassin but here, at age 37, they were clear,  focused, clinical and devoid of excess emotion.

focused, clinical and devoid of excess emotion.

He had a job to do and he knew exactly how to do it without wasting his limited energy supply. His extreme relaxation in the ring enabled him to outlast younger, more eager opponents, especially in the trenches. He also sensed that he was slightly behind entering the final six minutes and that he needed some of that old Duran magic to secure victory.

In the final minute of the 11th Duran connected with a heavy lead right that stunned Barkley, then a left-left-right that landed flush. Moments later, Duran reached back into his prime and produced a combination for the ages – an overhand right, a 45-degree hook, a right to the ear, a glancing hook and a scorching cross that floored Barkley and electrified a Convention Center crowd that fought through a snowstorm to secure their seats.

Barkley arose at Joe Cortez’s count of seven and managed to ride out the final seconds, but he unwittingly revealed his true state by twice failing to properly identify his corner.

Barkley arose at Joe Cortez’s count of seven and managed to ride out the final seconds, but he unwittingly revealed his true state by twice failing to properly identify his corner.

Barkley tried his best to pull himself together in the 12th and for the first two minutes he performed admirably. In the final 60 seconds, however, Duran’s shotgun jabs caused Barkley’s legs to shudder and his jolting rights at close range scored often enough to close the mathematical gap one final time. Only after the final bell sounded did Duran engage in vintage bravado as he stared daggers at Barkley while bouncing lightly on his toes.

The scorecards were split and widely divergent. Judge Dave Brown saw “The Blade” a 116-113 winner while Giuseppi Ferrari turned in a 118-112 card for Duran. Veteran jurist Tom Kaczmarek cast the deciding ballot of 116-112 for the winner – and new – champion.

With the victory Duran became only the third fighter – and the first Latin – to capture major titles in four weight classes. Moreover his championship arc was lengthened to a remarkable 17 years and the fight was declared THE RING’s 1989 Fight of the Year – Duran’s first and only such honor.

In reality Duran defeated two opponents this night – Barkley and Father Time.

2. June 16, 1983 – KO 8 Davey Moore, Madison Square Garden, New York, New York

Ever since the “No Mas” fight, Duran’s career and standing within the boxing community had spiraled into a deadly tailspin. Two uninspiring wins over Nino Gonzalez and Luigi Minchillo in 1981 was followed by a horrific 1982 that saw back-to-back losses against Benitez and Laing as well as the lackluster 10-round win over Batten on the Pryor-Arguello I card.

But through all the years Duran proved that when properly motivated he was capable of producing magical performances. When promoter Bob Arum arranged a crossroads fight with Pipino Cuevas in January 1983 Duran responded with the his best performance in years. He proved beyond doubt that something special still resided within and that he was worthy of a chance at redemption. Duran’s reward for beating Cuevas was a chance at capturing a third divisional championship and the target was WBA junior middleweight titlist Davey Moore.

Moore-Duran was originally scheduled for Sun City, Bopthuthatswana in South Africa as part of a championship doubleheader with WBA lightweight king Ray Mancini versus Kenny Bogner that was packaged with a Frank Sinatra concert. That event was canceled when Mancini broke his hand in training, so Arum moved Moore-Duran to Madison Square Garden. It was a natural fit, for Moore was a native New Yorker while Duran was a hero to the city’s Latin community. Moreover, the date of the bout – June 16, 1983 – just happened to fall on Duran’s 32nd birthday.

Moore was a cocky, well-muscled 24-year-old with great athletic talent. Despite taking up boxing at age 15, Moore became one of the rare fighters ever to capture four New York Golden Gloves championships and had he not clowned away a potential decision victory in the 1980 semi-finals he had a good shot of becoming the first man to win five. Mark Breland would earn that distinction a few years later.

As a pro Moore achieved historically instant success, for in his ninth pro fight he shockingly won the WBA junior middleweight title from Tadashi Mihara on Mihara’s home turf of Tokyo via sixth round TKO. At first Moore was seen as a paper champion but over the next 16 months he gained respect by beating top challenger Charlie Weir, former titlist Ayub Kalule and Gary Guiden – all by knockout. Entering the Duran fight, Moore had stopped his last nine opponents and he fully expected to make Duran number 10.

“Duran was a great lightweight, a good welterweight and a mediocre junior middleweight,” Moore told UPI. “There’s a big difference fighting people at 135 pounds and fighting them at 154. Not only can’t he be as physical, he’s a lot older now and he’s not as strong. I don’t think it will be all that tough a fight. He passed his peak a long time ago and I’m still getting close to reaching mine.”

“Duran was a great lightweight, a good welterweight and a mediocre junior middleweight,” Moore told UPI. “There’s a big difference fighting people at 135 pounds and fighting them at 154. Not only can’t he be as physical, he’s a lot older now and he’s not as strong. I don’t think it will be all that tough a fight. He passed his peak a long time ago and I’m still getting close to reaching mine.”

The bettors agreed with Moore as they installed him as a solid 5-to-2 favorite. But Duran, who promised he would retire if he lost to Moore, warned observers that appearances could be deceiving.

“Forget about those last few fights before Cuevas,” Duran said in the same UPI story. “I’m not the same person. I worked hard for the Cuevas fight because I knew it meant so much and I’ve worked even harder preparing for this one. I’m not fighting this fight for the money. I want to prove that I’m a champion. I’m doing this for the glory.”

“I never lost my punching power,” Duran continued. “The only difference was that I wasn’t training right. I wasn’t losing the weight properly. I was trying to take it off too fast and getting weak. This time my weight has been down for quite a while and I feel very, very strong.”

The weigh-in was revealing: Moore initially scaled 156 and was forced to boil down to 154 while Duran was a hard and ready 152¾. Although Moore was fighting at home, most of the 20,061 that packed the Garden – the first  sellout at MSG in 10 years – came to cheer their Latin legend.

sellout at MSG in 10 years – came to cheer their Latin legend.

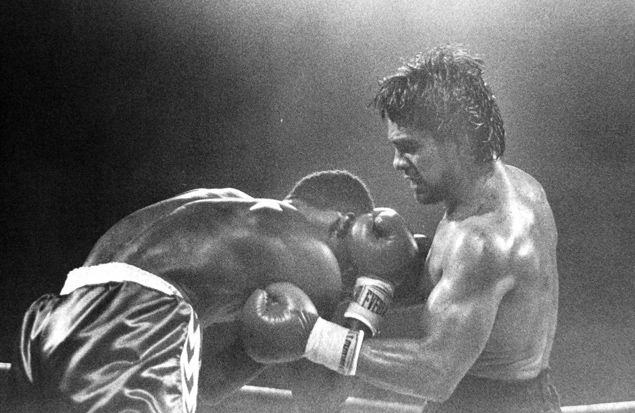

The fight began slowly as each man probed with jabs and circled each other in tight arcs. Moore had expected Duran to come straight at him but instead Duran threw off his timing with sage head and shoulder fakes. But with 10 seconds remaining in the opening round, Moore’s effort to slip Duran’s jab resulted in Duran’s thumb striking the champion’s right eye. Upon impact Moore, clearly bothered, squinted and lifted his glove toward the injury.

As the fight continued Duran’s blueprint emerged: Dart inside Moore’s punches and rip short blows to the jaw and ribs to soften up the champion over time. It didn’t take long for the damage to surface: Just five-and-a-half minutes into the fight Moore’s eye was swollen, his legs were tottering, his nose was leaking blood and most of his  punches flailed harmlessly off target. Meanwhile, Duran had turned back the clock to the pre-“No Mas” version of himself: Fast, fluid and ferocious. Every punch he landed seemed to hurt Moore and the champion’s agony only served to feed the beast that made Duran a legend in his own time.

punches flailed harmlessly off target. Meanwhile, Duran had turned back the clock to the pre-“No Mas” version of himself: Fast, fluid and ferocious. Every punch he landed seemed to hurt Moore and the champion’s agony only served to feed the beast that made Duran a legend in his own time.

“It looks like a master against a kid with 12 fights,” Gil Clancy exclaimed at ringside. “He’s taking him apart.”

As Duran’s successes mounted, so did the crowd’s frenzy. They chanted “Doo-ran! Doo-ran!” as the challenger repeatedly nailed Moore with flush power shots. Duran, who knew the sting of being a pariah, clearly fed off the crowd’s positive energy as well as the prospect of regaining everything he had lost in the Leonard rematch — money, power and respect. He was the perfect blend of science and savagery as he took Moore apart piece by piece. Every lesson he had learned in 80 professional fights was converging into a perfect storm, and Moore was its sole victim.

With 16 seconds left in round seven, a massive overhand right sent the beaten and exhausted Moore to the floor. With his right eye now completely shut, a blank-faced Moore pushed himself up at nine and the round ended without another punch thrown.

With 16 seconds left in round seven, a massive overhand right sent the beaten and exhausted Moore to the floor. With his right eye now completely shut, a blank-faced Moore pushed himself up at nine and the round ended without another punch thrown.

In his excitement, Duran accidentally sat down on Moore’s stool and a Duran second rushed across the ring to escort him to the correct corner. It was a comic moment in an event that had the potential to turn tragic. That’s because Moore’s manager/trainer Leon Washington chose to send his battered charge out for round eight.

“I had discussed stopping it with Davey the round before,” Washington told KO Magazine’s Steve Farhood. “I got a little concerned after the knockdown, but I hoped he would come out of it.”

By this point Moore could do no more than meekly wrap both gloves around Duran’s head. His hunched body was held up by legs that could barely function. For Moore it was the ultimate boxing nightmare: He was at the mercy of a fighter whose legend was built on a lack of mercy.

Duran smashed Moore’s head and body without pause and soon the cheers turned into pleas for compassion. Both Moore’s mother and girlfriend had fainted and referee Ernesto Magana not only allowed the carnage to continue, he actually warned the semi-conscious Moore about pushing.

“This is disgraceful,” CBS blow-by-blow man Tim Ryan declared. “I cannot understand or condone this referee’s activity and Moore’s corner should stop the fight.”

Just as he said that, Duran teed off with yet another flush right to the face. New York State Athletic Commissioner Jose Torres was among those who screamed for Magana to stop the carnage but the referee inexplicably remained a spectator. Finally, with a little more than a minute remaining in the eighth, a blood-soaked white towel fluttered into the ring. While Magana still didn’t stop the fight, it provided the cue for other officials to intervene and Duran’s corner to storm the ring.

With the victory, Duran joined Bob Fitzsimmons, Henry Armstrong, Tony Canzoneri, Barney Ross, Alexis Arguello and Wilfred Benitez as three-division champions. But for Duran it meant vindication, replenished riches and more chances to write his own fistic legacy.

The post-fight scene was unforgettable: As the crowd chanted his name, a teary-eyed Duran stood on the ring apron and joined in. Then Duran was serenaded with an impromptu rendition of “Happy Birthday.” The object of their affection couldn’t have imagined a better way to celebrate the start of another year on earth.

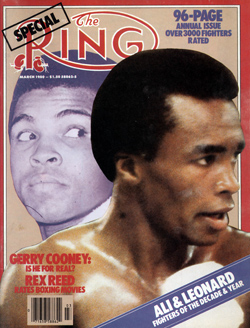

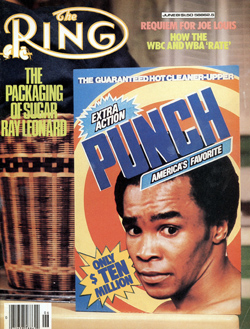

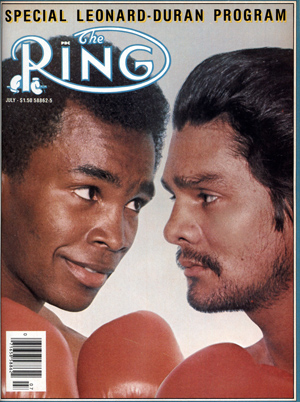

1. June 20, 1980 – W 15 Sugar Ray Leonard I, Olympic Stadium, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

In the year since beating Carlos Palomino to earn the WBC’s mandatory ranking Duran fought three times, winning all three and scoring two knockouts. He was initially troubled by the taller Zeferino Gonzalez’s speed but still won a wide 10-round decision while against Joseph Nsubuga (KO 4) and Wellington Wheatley (KO 6) he showed enough to earn victory without exhibiting every signature skill. Critics said Duran lacked the fire and punch of his lightweight days but they also knew Duran saved his very best stuff for his very best opponents.

For that reason, those same critics still saw a showdown between Duran and WBC champion Sugar Ray Leonard as the decade’s first “dream match.”

For that reason, those same critics still saw a showdown between Duran and WBC champion Sugar Ray Leonard as the decade’s first “dream match.”

The 24-year-old Leonard was a brilliant fighting machine. Standing 5-feet-10 and armed with a 74-inch reach, “Sugar Ray” was the quintessence of the perfect welterweight in terms of physique and proportion.

His punches had comet-like speed, his legs were Astaire-like and his ring acumen was advanced. He also was growing as a fighter, for in his first defense against Dave “Boy” Green Leonard answered those who questioned his punching power with a terrifying one-punch knockout in round four that left the Briton unconscious for several worrisome moments.

But as formidable as Leonard was physically, his persona was even more impressive.

His megawatt smile and pleasant on-camera demeanor moved ABC’s Howard Cosell to embrace his cause during his run to Olympic gold at the 1976 Montreal Olympics and, with the considerable help of lawyer Mike Trainer, his business acumen was such that he re-wrote the book on how to market a fighter. Instead of signing with a single promoter, Leonard formed his own corporation and sold his services to the highest bidder. The results were extraordinary: Not only did Leonard achieve generational wealth before age 25, he also was poised to replace the iconic Muhammad Ali as the face of boxing.

Duran saw all this and seethed.

He perceived Leonard as many critics did: A spoiled, over-praised “creation of television” that had everything handed to him and an American darling that embodied the country’s excesses.

He perceived Leonard as many critics did: A spoiled, over-praised “creation of television” that had everything handed to him and an American darling that embodied the country’s excesses.

Duran also was profoundly insulted by Leonard’s elevation by the media, for he, Carlos Monzon, Jose Napoles and other international stars were swallowed up by Ali’s all-consuming shadow for more than a decade. With Ali finally gone, Duran believed he should have occupied Ali’s vacated spot but instead that title was handed to Leonard. Finally, many Panamanians harbored animus toward Americans for their control of the Panama Canal. Writer Pete Hamill once told Dick Schaap on Classic Sports Network (the forerunner of ESPN Classic) that at age 11 or 12, one of Duran’s favorite pastimes was to wander into Panama City, find the first big, drunken American sailor he could find and knock him out.

“That was Duran’s way of saying, ‘you guys have the power and the guns but we can punch, too,'” Hamill said.

The pre-fight mind games were as torrid as the fight promised to be. Leonard believed he achieved the upper hand by securing a deal that had Leonard making a minimum $7.5 million to Duran’s $1.5 million as well as having the fight staged in Montreal, the site of Leonard’s Olympic triumph. Additionally, Leonard sought, and got, a spacious 20-foot ring that would amplify his superior mobility. But Duran proved more than a worthy adversary on the psychological front. He unnerved and angered Leonard with gutter language in the pre-fight press conferences that included vulgar references to Leonard’s wife. Also, he instantly won the favor of the Quebecois by wearing a T-shirt bearing the word “Bonjour” during public workouts and greeting them with a few words in their native tongue. Duran was in full control of the pre-fight messaging and Leonard admitted in later years that Duran’s act had gotten to him mentally.

By fight night Leonard felt empty and out-of-sorts. He believed strongly in biorhythms and he knew that all three cycles — physical, emotional and intellectual — were down. He also was stunned at the boos that greeted his arrival and at the deafening cheers that Duran, the 3-to-2 underdog, received. The cold, clammy air that swirled about the outdoor stadium only added to his unease. Meanwhile, Duran and his camp were in top form and ready to go. Chief second Ray Arcel delivered a brief pre-fight lecture to referee Carlos Padilla to ensure that the third man, known for breaking fighters quickly as was the case in the recent Alan Minter-Vito Antuofermo fight, would “not take the inside away” from Duran. Duran, for his part, was primed for combat and once the bell sounded he finally released the fury that raged within.

By fight night Leonard felt empty and out-of-sorts. He believed strongly in biorhythms and he knew that all three cycles — physical, emotional and intellectual — were down. He also was stunned at the boos that greeted his arrival and at the deafening cheers that Duran, the 3-to-2 underdog, received. The cold, clammy air that swirled about the outdoor stadium only added to his unease. Meanwhile, Duran and his camp were in top form and ready to go. Chief second Ray Arcel delivered a brief pre-fight lecture to referee Carlos Padilla to ensure that the third man, known for breaking fighters quickly as was the case in the recent Alan Minter-Vito Antuofermo fight, would “not take the inside away” from Duran. Duran, for his part, was primed for combat and once the bell sounded he finally released the fury that raged within.

Leonard began the fight unusually flat-footed, choosing to circle Duran in small arcs while Duran cut the ring and sought the best angles to rush inside. Following a close first round, the fight’s first seminal moment came midway through round two when a sweeping hook buckled Leonard’s legs. Duran was on his prey in a flash, driving a left-right to the body and bulling Leonard to the ropes. Padilla, heeding Arcel’s words and remembering the criticism he received for his handling of Minter-Antuofermo I, barely tried to break the pair and backed away when neither man stepped away.

That moment defined the terms of battle and Duran exploited them in every conceivable way. Duran used his arms, shoulders and head to bull Leonard about the ring and Leonard, knowing he was confronted with a “fight or die” proposition, did his best to retaliate within the confines of his environment. Beginning in round three, Duran trapped Leonard on the ropes and conducted a master class on infighting. He drove both hands to the body, used his head to scrape the skin around Leonard’s eyes raw and pivoted from side to side to block Leonard’s escape routes. Duran’s superb upper body movement effectively foiled Leonard’s attempts to punch his way free. The trench warfare continued even at ring center, for Leonard was determined to match macho with macho.

At times Leonard tried to obey Angelo Dundee’s demand to box Duran but “Sugar Ray” eventually was sucked back into Duran’s Lamotta-esque in-fighting game. Occasionally Leonard’s wonderful skills produced moments of brilliance but as a whole they were too fleeting to make an impact on the scorecards. Leonard overcame a heavy right in the fourth that hurt him a second time to spark a wondrous end-of-round exchange and a jolting hook to begin the fifth appeared to stun Duran. But Duran’s comparable hand speed and far superior experience were more than a match for Leonard’s youth and otherworldly talent.

The pace was relentlessly torrid and it severely tested each man’s resolve. Both strained under the brutality but each rose above it with skill, smarts and stamina. Duran stretched his lead in the middle and late rounds though the 11th and 13th rounds were tremendously action-packed sessions that pushed both fighters beyond previously thought-of limits.

The pace was relentlessly torrid and it severely tested each man’s resolve. Both strained under the brutality but each rose above it with skill, smarts and stamina. Duran stretched his lead in the middle and late rounds though the 11th and 13th rounds were tremendously action-packed sessions that pushed both fighters beyond previously thought-of limits.

Leonard produced an inspired rally in the 14th and 15th but his efforts weren’t enough to snatch away Duran’s victory. In the final 10 seconds a swaggering Duran tapped his chin with his glove, fired three jabs, danced away and brusquely batted away Leonard’s congratulatory glove. With raw emotion pouring from him he leaped into the air, shoved the passing Leonard’s shoulder and cursed at top volume. It was Duran at his rawest and yet it was also Duran at his greatest.

Although the decision was announced as split it actually was unanimous. Angelo Potelli indecisively saw it 148-147 — he scored 10 rounds even — while Raymond Baldeyrou (146-144) and Harry Gibbs (145-144) agreed that the onetime lightweight champion was the new welterweight champion.

Duran’s performance was truly historic, both aesthetically and factually. As he celebrated his 41st consecutive victory inside that Montreal ring, Duran’s record stood at 72-1 (57). By beating Leonard, Duran joined Barney Ross as the only previous lightweight champion to win the welterweight title, for Henry Armstrong, who later won a lightweight belt, actually was the reigning featherweight king at the time he dethroned Ross.

Though no one knew it at the time, it also was the final time boxing fans witnessed Duran in his purest form in terms of public standing. The greatest lightweight in history in many eyes now was now making his case at welterweight and he did so with the best performance of his career. It epitomized every aspect of Duran’s legend and he secured this landmark achievement against a fantastically equipped rival in Leonard. The events of their rematch five months later would permanently, but not irreparably, stain that reputation but in terms of performance level against a worthy rival, Duran’s fight against Leonard proved beyond doubt that few ever did it better than Roberto Duran.

*

Research sources used include:

“Hands of Stone: The Life and Legend of Roberto Duran” by Christian Giudice

“In the Corner: Great Boxing Trainers Talk About Their Art” by Dave Anderson

“The Big Fight: My Life in and Out of the Ring” by Sugar Ray Leonard

with Michael Arkush

“25 Years Later: Duran vs. Moore Remembered” by Lee Groves

“A Passion Ignited: A Writer’s Thunderbolt Moment” by Lee Groves

Photos / THE RING, AFP

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, W.Va. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 10 writing awards, including seven in the last three years. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. He is the author of “Tales From the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics. To order, please visit Amazon.com or e-mail the author at [email protected] to arrange for autographed copies.