Muhammad Ali: Global Icon

Editor’s note: This feature originally appeared in the November 2016 issue of THE RING Magazine.

The heavyweight champion of the world.

Let’s take the title literally for a moment. There have been countless heavyweights and dozens of champions, but how many of them have been able to transcend national and cultural boundaries? How many have been able to fuse the world of sports with the turbulence of the times to emerge as a never-to-beforgotten and cherished global figure?

Muhammad Ali’s passing on June 3, 2016, at the age of 74, reminded everyone just how much the former three-time heavyweight champion of the world meant to people of every race, creed and color. It is an impossible task to capsulize all of the reasons this is the case but it’s a story that goes back over half a century and one could be forgiven for believing that it was preordained.

“First, you have to consider the medium,” said Ali’s biographer and close friend, Thomas Hauser. “Ali came along in 1960, just as television was growing out of its infancy. For the first time, television was learning not just how to transmit very basic things but how to identify and build stories. Then, of course, satellite technology came in.

“When Ali won gold at the Rome Olympics in 1960, ABC television had to drive the tape to the airport, put it on a plane, have someone pick it up and bring it back to the studio. Five years later, you could see things like that instantaneously. This enabled Ali’s global reach.”

Cassius Clay, as he was known at the time, was merely a gifted fighter for 3½ years. Then, following his dramatic title victory over Sonny Liston on February 25, 1964, his face appeared on the front pages as much as it did the sports pages. Clay officially announced his conversion to Islam, changed his name to Muhammad Ali, and just as his skills reached the level of otherworldly he made a conscientious decision that cost him his athletic prime.

Mark Naison is a professor of African-American studies and history at Fordham University in New York and his knowledge of Ali’s downtime is extensive.

“Between 1964 and 1967, Ali was in limbo between being an incredibly appealing boxer and a somewhat controversial racial figure,” Naison said. “But when he resisted the draft, that’s when he became larger than life to an entire generation of young people, including whites, who had also resisted the Vietnam War. This gave him an incredibly broad-based appeal.

Ali – The People’s Choice. Photo by THE RING

“He had the glamour, the charisma and the controversy but the courageous decision to give up his title was something else. This was at a time when a lot of people I knew were going to jail or moving to Canada to avoid being drafted. There were anti-war demonstrations all over Europe, in South America, in Japan, and in many ways Ali became the most recognizable symbol of the anti-war movement.”

Ali was a pariah in his home country. Following his famous “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong” remark in early 1966, the heavyweight champion of the world was forced to defend his title outside America on four consecutive occasions. He beat George Chuvalo in Canada and Karl Mildenberger in Germany that year. Sandwiched between those defenses were two successful U.K. assignments against Henry Cooper and Brian London.

“He was actually hated in huge chunks of the United States because of his stance on the Vietnam War,” said Hall of Fame boxing writer Colin Hart. “In Britain, however, we believed in what he said because our prime minister at that time, Harold Wilson, kept us out of that war. Virtually nobody held the draft controversy against Ali because we believed he was right.

“We learned to love him. Why? Because Ali was the most charismatic sportsman of all time and had people eating out of his bloody hand. He was very good-looking so the women loved him even though they didn’t know a left hook from a coat hook. Following the Cooper rematch in 1966, he appeared on the Eamonn Andrews TV show and that changed people’s perceptions of him. He was so funny, so witty and so lovable that attitudes towards him literally changed overnight.”

Ali was stripped of his title in April 1967 and it would be 7½ years before he regained it. The Rumble in the Jungle, on October 30, 1974, is remembered for Ali’s sensational eighth-round knockout of George Foreman and his rope-a-dope strategy but the location of that contest had enormous significance.

“It was the first heavyweight championship fight to take place in Africa and that was Ali’s way of marking his sense of racial pride,” Naison said. “People of African descent were now a central part of the world of sports, the world of politics and the world of media.

“In Africa, where you have all these authoritarian regimes and dictatorships, Ali was seen as a model for people who wanted their own freedom. Most of Africa was living under European colonialism for close to 100 years before the independence movement of the ’50s and ’60s. Now here is this African- American who stood up to the most powerful forces in his country and survived. It’s a dual appeal: He’s a symbol of freedom for all people but particularly to people of African descent, given their own history.”

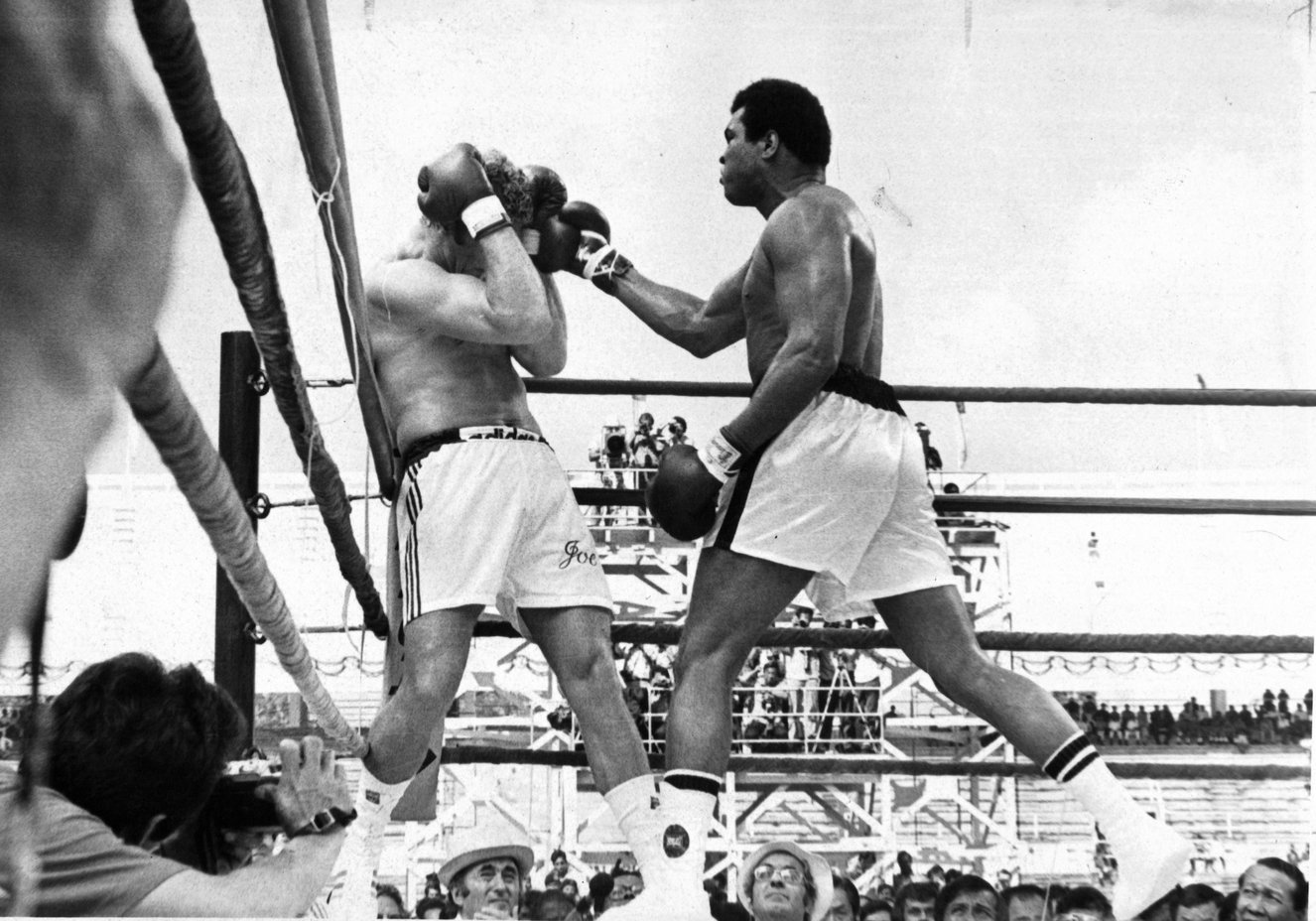

Ali (right) opens up on Joe Bugner in their rematch in 1975. Photo by THE RING

Eight months after regaining the title from Foreman, Ali would take on Joe Bugner. The pair had met in Las Vegas two years earlier and Bugner, who was criminally underrated throughout his own career, gave a good account of himself in a 12-round non-title bout that he lost on points.

The rematch would take place in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, a Muslim country, where Ali was idolized. However, the champion’s immense popularity took a sinister turn when one overly enthusiastic fan made contact with his opponent.

“We received a death threat at the hotel and handed it over to the police,” said Bugner, who was advised of the possible repercussions if he were to dethrone the great Ali. “After that, on the day of the fight, there were 200 Marines stationed at the stadium with telescopic rifles. When I saw all of that security I felt pretty safe but then I got to thinking, ‘It only takes one bullet to kill me.’

“The fight took place at 10:30 in the morning, so I thought maybe the crowd won’t be that big. I should have known better because when we got the stadium, there were 40,000 people there and 200 million watched the fight on closed circuit. Ali had such magical contact with the human race. He was beautiful and when you were near him, he just gave off this incredible magnetism. It didn’t matter where he was, people just gravitated to him and that never changed.”

Bugner lost a unanimous decision and three months later Ali was globetrotting again. In October 1975, the Philippines was an impoverished country struggling for survival under the Ferdinand Marcos regime. Rebels were fighting in the mountains and hundreds of people were being killed but, remarkably, a third fight between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier was enough to bring about a temporary ceasefire.

Ali, at this point of his career, was arguably the most famous man on the planet and perpetually in demand. Hart, who covered The Thrilla in Manila from ringside, recalls the champion taking big chances with an obsessed fan base.

“While we were in Manila, there was this terrible outbreak of conjunctivitis and Ali was due to go (on a) walkabout one day,” he said. “Ferdie Pacheco, Ali’s doctor, warned him not to go anywhere near children who could be infected because that disease is very contagious and if Ali caught it, the fight would have been off. Of course Ali gets to Quezon City, gets out of the limo and the first thing he did was kiss a child.

“He had such an affinity with people and you can’t control or manufacture that.”

Ali (center) appears on The Tonight Show in 1976. Photo by THE RING

Ali won The Thrilla in Manila in 14 rounds but lost a huge portion of his physical resources in a horrifically violent encounter. He fought on until 1981 and after his professional career had ended, his health declined quite rapidly. But even as that magnificent physique crumbled and that booming voice became a whisper, he still reigned supreme in terms of global popularity.

What Ali could no longer do physically, he did spiritually. Can you think of another athlete or celebrity who could have traveled to Iraq and negotiated the release of 15 American hostages from Saddam Hussein? Ali did that in November 1990, six weeks before the United States began dropping bombs on January 17, 1991.

Later that same year, Hauser traveled to Jakarta, Indonesia, with Ali and recalls the incredible hysteria that surrounded the former champion. “We went to the Grand Mosque and when word got out that Ali was there, literally 200,000 people turned up,” he said. “The government had to send in troops to get us out because all of these people had literally surrounded the mosque. They put Ali in a military vehicle and drove him out and I got left behind. Luckily someone recognized me and gave me a ride back to the hotel.

“It was extraordinary, the hold he had over the world. Even the people who didn’t like Ali, liked Ali. He stood as a beacon of hope for oppressed people all over the world when he refused to be inducted into the army. He stood up for the proposition where unless you have a very good reason for killing people, war is wrong. Ultimately he became the personification of goodwill and love, and on top of that he was arguably the greatest fighter of all time.”

And therein lies the answer as to why Muhammad Ali is essentially a world treasure. As a heavyweight fighter, he could do things that no one else could do and he made boxing look beautiful. Inside that movie star exterior was an engine of warrior courage and heart, attributes that Ali exhibited all over the world, inside and outside of the prize ring.

“There’s no one like him,” Naison said. “There’s no other boxer with that charisma. There’s no one who spoke up on political issues the way he did. There’s no one who could hold their own with any elected official or talk show host like he did. He was a completely unique figure in terms of how he looked in the ring and how he conducted himself outside of it.

“He’s up there with Martin Luther King and Malcolm X as someone who changed race not only in America, but globally, and he did that from the unprecedented posture of being a professional athlete. That has never been done before or since.”

Tom Gray is a UK Correspondent/ Editor for RingTV.com and a member of THE RING ratings panel. Follow him on Twitter: @Tom_Gray_Boxing

Struggling to locate a copy of THE RING Magazine? Try here or…

SUBSCRIBE

You can subscribe to the print and digital editions of THE RING Magazine by clicking the banner or here. You can also order the current issue, which is on newsstands, or back issues from our subscribe page. On the cover this month: Vasyl “Hi-Tech” Lomachenko.