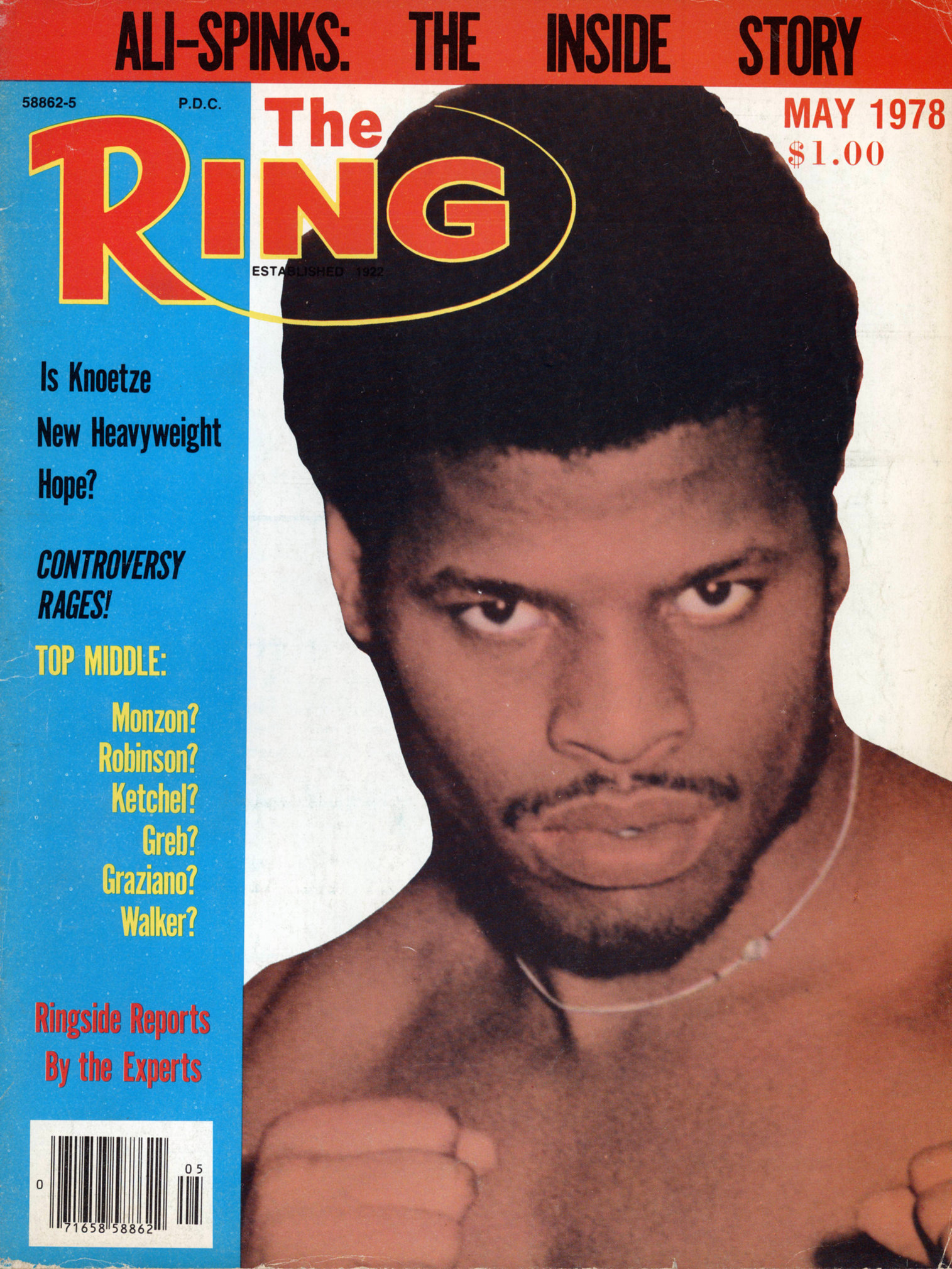

Muhammad Ali-Leon Spinks: The only time Ali lost his title in the ring

At 36 years of age, the great Muhammad Ali was on the physical descent.

The warning signs were clearly visible in prior defenses of his heavyweight championship. Jimmy Young and Ken Norton could easily have been given decisions against Ali in 1976. A European-level fighter like Alfredo Evangelista could last the distance in May 1977. And power-puncher Earnie Shavers, despite falling short on points, had inflicted 10 fights worth of damage on “The Greatest” over 15 brain-shuddering rounds that September.

Ali, who should have been enjoying retirement, needed a very easy fight – enter Leon Spinks.

The St. Louis product was a decorated amateur star. He had captured bronze at the World Championships in 1974, silver at the Pan-Am Games in 1975 and gold, as a light heavyweight, at the Montreal Olympics in 1976. Great stats, but, alarmingly, the challenger was bringing a (6-0-1, 5 knockouts) professional record into a heavyweight championship fight.

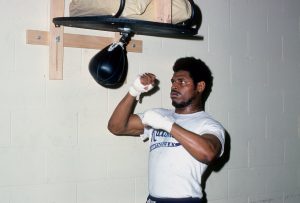

Spinks in training for the first Ali bout. Photo by THE RING Archive

The 24-year-old Spinks would be the most inexperienced professional to vie for the title since Washington’s Pete Rademacher. In August 1957, Rademacher, a former Olympic gold medalist from Melbourne 1956, made his professional debut against then-heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson. The challenger was on the cusp of a dream victory when he floored Patterson in the second stanza, but the humiliated champion paid Rademacher back in full, flooring him six times en route to a sixth-round knockout.

Spinks had looked better than average since turning professional in January 1977, but a draw against Scott LeDoux, who had lost five of his prior eight outings, was a disastrous result. The world media approached the Ali-Spinks bout with dread, and Ali was so embarrassed by the pending contest that the normally bombastic champion barely uttered a word during the buildup.

Ali, with nothing to get up for, trained half-heartedly. The challenger, with the gold encrusted opportunity of a lifetime, went through hell on earth to ready himself for 15 rounds of combat. Spinks had never been beyond 10, whereas Ali had gone 15 full rounds on 10 occasions. This was the one statistic that the Ali camp was banking on and that turned out to be a big mistake.

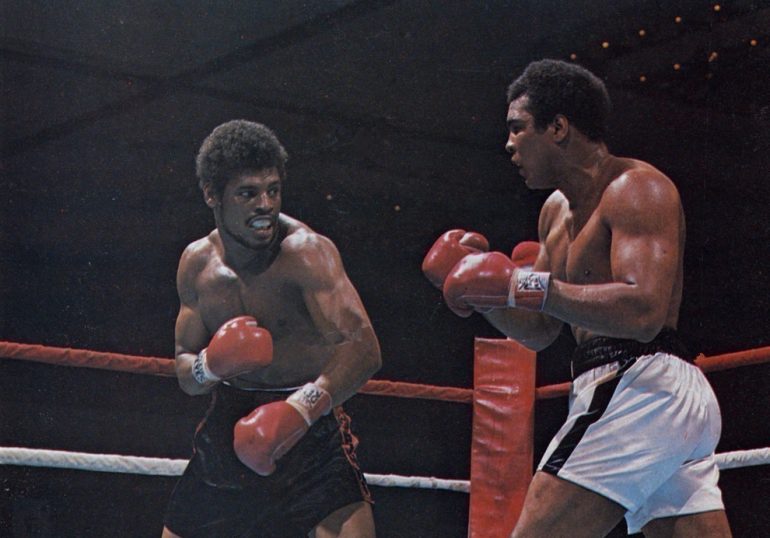

The fight took place at the Las Vegas Hilton on February 15, 1978. And what an undercard. Future light heavyweight and heavyweight champion Michael Spinks, Leon’s brother, won an eight-round decision. Michael’s future rival, Eddie Mustafa Muhammad, then fighting as Eddie Gregory, bounced back from a world title defeat to Victor Galindez to win a 10-rounder. And future undisputed middleweight champion Alan Minter knocked out Sandy Torres in five.

Ali entered the ring to Land of Hope and Glory, which was ironic given what was about to unfold. The great champion looked almost bored as he walked the length of the ring to shake hands with Spinks, who was in the process of applauding his long-time idol.

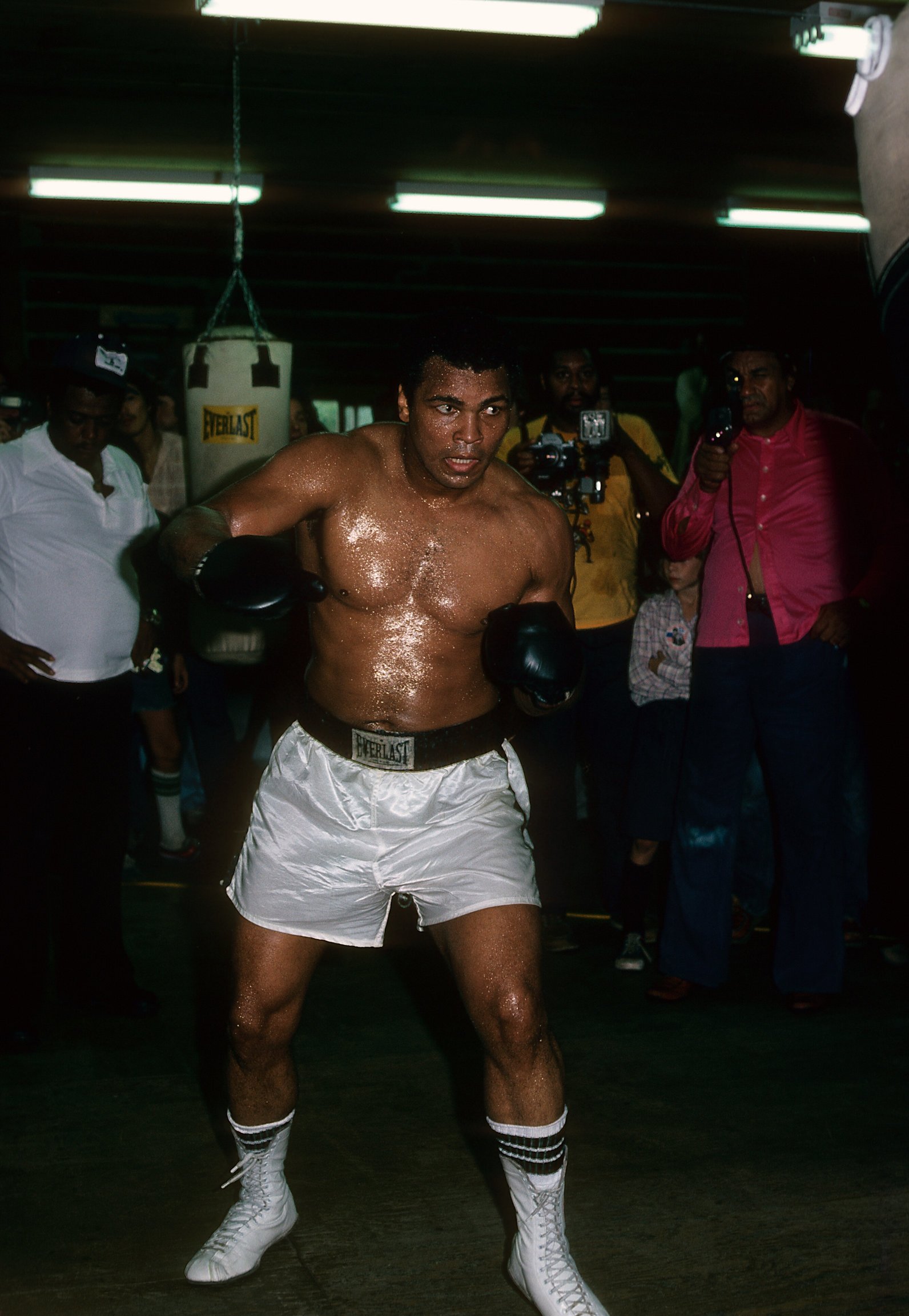

Ali in training for Spinks at his camp in Deer Lake. Photo by THE RING Archive

Ring announcer Chuck Hall revealed the weights: Spinks, who at 197¼ pounds could have entered today’s WBSS cruiserweight tournament, and who would later campaign at the old 190-pound limit, was in excellent fighting shape. Ali, looking fleshy, had weighed in at a pretty standard – by that time – 224 ¼ pounds.

At the opening bell, Spinks rushed out and fought like it was do or die. The tactics were straight punching and rolling at ring center, and when Ali sought refuge against the ropes, switch to hooks and uppercuts to head and body. It was a near-impossible pace and Ali, by way of response, could only talk, tease and cover up while the challenger teed off on the target.

This was the famous rope-a-dope strategy that had bedeviled George Foreman four years earlier in Zaire. Now, it was Ali’s curse. He had fallen in love with the idea of tiring out the opposition, just like he had Foreman, before rallying back to win sensationally. The problem was that it didn’t always work. The likes of Frazier, Norton and Shavers found gaps and punished Ali heavily. And for a young tiger like Spinks, the rope-a-dope was an open invitation to kick Ali’s ass and that’s just what he did.

The other thing working against the champion was that referee Davey Pearl would not allow him to hold. If you look back on the second part of Ali’s career, holding – although illegal – was often crucial. New York referee Arthur Mercante worked Ali’s first bout with Joe Frazier and his third against Norton. In both fights, Mercante threatened to deduct points for clinching. Ali, as a result, was forced to work harder than he wanted to and struggled in those fights. Now, compare that to Ali-Frazier 2, where referee Tony Perez allowed Ali to hold a total of 133 times (Frazier’s trainer, Eddie Futch, counted). “The Greatest” had a much easier time.

In this fight, Spinks was being allowed to work up-close unmolested and his opponent was feeling it.

By the midway point, Ali sensed that the challenger had an extra tank of gas and there was now some urgency. He moved on Spinks and let his hands go more often, however the punches produced very little damage. Ali enjoyed a big 10th and was imposing his boxing skills on Spinks, but he couldn’t keep up the charge and the younger man continued to make a strong impression.

The championship rounds smacked of irony. In 15-round contests, with very few exceptions, Ali had always closed extremely well. It was part of his DNA as a ring warrior. In this fight, however, the novice was outpunching the battle-hardened veteran down the stretch. This was akin to a capable middle-distance runner outlasting an elite-level marathoner over the last mile. Youth was getting the better of experience when it mattered most.

The 15th round was a classic. Ali came out blazing; smashing Spinks with everything in the arsenal, including body shots – a rarity – and brutal right hands to the point of the chin. However, the final three minutes were simply a metaphor for the entire fight. Ali tried to turn the clock back and the challenger pushed it forward again. In the closing 30 seconds it was Spinks who would not be denied. He rattled the champion with a stunning left uppercut and a big right hand on the bell.

The 15th round was a classic. Ali came out blazing; smashing Spinks with everything in the arsenal, including body shots – a rarity – and brutal right hands to the point of the chin. However, the final three minutes were simply a metaphor for the entire fight. Ali tried to turn the clock back and the challenger pushed it forward again. In the closing 30 seconds it was Spinks who would not be denied. He rattled the champion with a stunning left uppercut and a big right hand on the bell.

Spinks had won over Ali, but could he win over the judges? The bout was officially declared a split decision, but Art Lurie’s 143-142 card in Ali’s favor was frankly hideous. Referee Pearl and Harold Buck handed in scores of 145-140 and 144-141 respectively in favor of the new champion – Leon Spinks. Upon scoring the bout again, my card was in line with that of Buck’s, and there’s no way I could justify an Ali victory.

If you haven’t seen Ali-Spinks, or if you haven’t seen it in a long time, it’s worth revisiting. In fact, the matchup would later win THE RING Fight of the Year and THE RING Round of the Year (15). I would have no major complaint about either of those awards had it not been for the fact that Larry Holmes won the WBC heavyweight title from Norton that year, cementing his victory with what was arguably the greatest 15th round ever contested.

The Spinks-Ali rematch took place seven months later in New Orleans and it was a very different contest. In between fights, Spinks had found more trouble outside the ring than he ever could within it and his performance suffered as a result. Ali maintained tactical superiority throughout; jabbing off Spinks, tossing in the occasion right and – yes – holding. Referee Lucien Jubert penalized Ali a round (the fifth) for the infringement, but Ali banked enough sessions legitimately to claim a one-sided unanimous decision.

To this day, Ali is the only man to win the lineal heavyweight championship of the world on three occasions.

*Editor’s Note: After defeating Ali, Spinks was stripped of the WBC title for refusing to fight their No. 1 challenger, Ken Norton. The Spinks-Ali rematch was for THE RING and WBA titles only. Norton was upgraded to full WBC titleholder and lost in his first defense to Holmes on June 9, 1978.

Tom Gray is Associate Editor for THE RING. Follow him on Twitter: @Tom_Gray_Boxing

Struggling to locate a copy of THE RING Magazine? Try here or

Subscribe

You can order the current issue, which is on newsstands, or back issues from our subscribe page.