Here’s a Muhammad Ali project that brings plenty new to the table

There was an interesting reaction when HBO said they’d be showing a documentary on Muhammad Ali, back in February, called “Ali & Cavett: The Tale Of The Tapes.” Some folks, people who would be good candidates to tune in, in theory, felt that there’d been enough Ali docs, and HBO had screened plenty of them.

What else, some said, was there to be learned about the man whose peak came 45 years ago, who died in 2016?

I watched and didn’t dislike the production, because the doc focused on archival footage, material that hadn’t been in circulation. But anyone doing an Ali doc, or a book on “The Greatest,” will be faced with the basic question: can I bring something new to the table?

When author Todd Snyder, a writing professor at Siena College in Albany, NY decided to go there, and do “an Ali book,” he didn’t need to engage in too much self scrutiny. Snyder’s effort, published by Hamilcar Publications in Boston, “Bundini: Believe the Hype,” is a deep dive on a capital “C” character, “Bundini” Brown,” a worthy subject that hasn’t been over-mined.

Here is a Q n A with the author, who is finishing up “Beatboxing: How Hip Hop Changed the Fight Game,” which comes out in 2021.

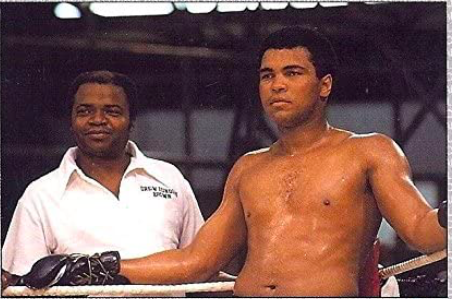

Q: Big old contention on the front cover…”Bundini was the source of Muhammad Ali’s spirit.” One hundred percent true? Or a certain percentage? If wholly true, then it wasn’t a moment too soon that someone decided to go all in and examine this Drew “Bundini” Brown!

A: That quote was given to me by George Foreman. I’d asked Big George how he would personally define Bundini’s role in Ali’s life. Bundini wasn’t a boxing trainer, not in the traditional sense. Foreman’s phrasing struck me because the word “spirit” also showed up in responses offered up by Khalilah Camacho-Ali, Larry Holmes, Gene Kilroy, James “Quick” Tillis, and a few others. Quick Tillis specifically used the term “Spirit Coach,” I believe. Bundini wasn’t the only source of Muhammad Ali’s spirit, of course. Ali had plenty of spirit before he ever met his poetic corner man. Bundini was a key piece to the puzzle, however. He was a natural born motivator. He charged Ali’s batteries, as Angelo Dundee once stated.

Q: How did “Bundini” as a subject come to you? Are you a “boxing guy,” and were you always curious to learn more about that hype man who Ali seemed to sync so hard with?

A: Now that my book is out in the world, I am occasionally asked some variation of this question: What motivated an English professor to write Drew Bundini Brown’s life story? First, I’m the son of a small town boxing trainer, Mike “Lo” Snyder. Ali was my father’s hero. Lo’s Gym, my father’s boxing club, was a pillar in our poor mountain community in rural West Virginia. A few years back, I wrote a memoir titled “12 Rounds in Lo’s Gym: Boxing and Manhood in Appalachia” (West Virginia University Press, 2018).

Author Snyder put out “12 Rounds in Lo’s Gym”in 2018. His dad Mike “Lo” Snyder is a fifth-generation West Virginia coal miner who ran boxing gyms that catered to have not kids in an underdog region of America.

In retrospect, my life has always centered on the sport. I boxed when I was a teenager. I spent years working corners with my father. I spent years assisting in the gym as well. Because of my background, I’ve always been interested in trainers and training camps. I see the sport of boxing through this particular lens. Oddly enough, my father nicknamed one of his assistant trainers, Jeff “Bundini” Dean. Jeff was my father’s most loyal sidekick. Second, I am a professor who publishes scholarship on hip-hop culture. I teach courses on hip-hop history as well. Bundini had a foot in both worlds, boxing and hip-hop. Scholars have ignored Bundini’s influence on Black culture. He was hip-hop before there was such a thing. As a hip-hop scholar, I wanted to fill this obvious research gap. There isn’t a reputable hip-hop history book that doesn’t acknowledge Ali’s impact. Both he and Bundini are pre-hip-hop cultural icons.

Q: I didn’t expect to be clued in to the reality of who that hype man was by the man’s son. Drew Brown III has had quite an interesting life arc himself. Did he emerge right away to you as being such a potential focal point in the project?

A: As a writer, I’ve always been drawn to stories of fathers and sons. Shortly after meeting Drew Brown III I decided the best way to tell his father’s story was through his eyes. Bundini has this wild, larger than life, persona. I wanted readers to view him as a man. He was a son, a husband, a father, and a friend. I wanted to afford my readers the opportunity to connect with Bundini intimately, on a more personal/familial level. I wanted readers to see him as Drew Brown Jr., not Bundini Brown. His son, as you suggested, has lived an extraordinary life. He was a first-generation college student, a college basketball star, a Navy jet pilot, a best-selling author and motivational speaker. Nobody knew Bundini better than his son. Early on, I realized this was the best way to reintroduce Bundini to the world.

Q: Handling of a subject is likely to be very different depending upon whether the subject is alive, or not. Ali died in 2016, at age 74. “Bundini” died in 1987, at age 59. The number of folks who were in the rooms when those two interacted has diminished. That makes getting a history harder. But, sometimes, the more time passes, the easier it is to get to harder truths. Can you tell us about the “timing” dynamic, and share some behind the scenes on the process to get to your most salient takeaways that you passed on to us?

A: As you suggested, so many members of Ali’s entourage are no longer with us. I was, however, given something of a time machine. Thanks to Drew Brown III, I was granted access to a treasure trove of Bundini artifacts, personal writings, letters, postcards, and other intimate documents. I even held Bundini’s famous Star of David necklace in my hands. Because of my connection to Drew Brown III, I was also given access to his mother’s artifacts. Bundini, as you know, married a white Jewish woman named Rhoda Palestine. Reading her words, interviewing members of her family, was also very helpful. If I had approached Drew Brown III ten or fifteen years ago, I don’t think he would have been emotionally ready for this journey. My research took him back to some very difficult times in his childhood. We don’t hide his father’s struggles. I think distance, in this particular instance, made talking about hard truths much easier.

Q: Several times in the book you did “Bundini” a solid, you corrected the record, or persistent chatter, about something he supposedly did or didn’t do. Did you feel a sense of duty to do that, maybe more so after hopping in, and discovering the depth to “Bundini?”

A: No. That wasn’t my intention. I didn’t feel it was my duty either. I came into this project believing, for the most part, all I had read about him. I didn’t enter the project looking to disprove anything. After the research began, I did, however, find those discrepancies fascinating. As an academic researcher, I think of scholarship as a discourse community, a parlor conversation of sorts. Many of the stories I have collected from Bundini’s son, and other members of the Brown family, do offer new perspectives. I offer those stories as counter-arguments to a conversation that already existed prior to my book. The reader ultimately gets to decide which narrative is more reliable. After getting to know the family, and other Ali-insiders, I quickly learned that some Bundini stories are easily disproved.

Q: And this is a weird question, there’s no good reason for asking it, but WTF. Do you believe in ghosts? Bundini strikes me as the kind of guy who would re-appear in ghostly form, and tell you that you done good with the book.

A: Ha! That might be the best question anyone has asked thus far. No, I’m not the kind of guy who believes in ghosts. But, I will tell you that, over the two year period that I was working on this book, Bundini showed up in a few of my dreams. I relayed these dreams to Bundini’s son. In each dream, Bundini showed up in the West Virginia trailer park where much of my childhood took place. I told Drew that I felt like his father was researching me.

While you have me thinking superstitiously, I do recall a recent incident where I was taking part in a Zoom interview with Paul Grondahl, director of the New York State Writer’s Institute. During the interview, I was explaining how Bundini referred to God as “Shorty.” In the middle of my explanation, three books fell off the side of my bookshelf. Paul, who could see what happened, stopped dead in his tracks and said, “do you think that was Bundini?”

Q: No excuse, in my mind, for Ali to slap “Bundini,” as you laid out on p. 214. You turned in the manuscript awhile back…Now that you’ve gotten more distance from the writing experience, how do you view that slap, and the underpinnings to this show of physical and psychological force. Was there a more sadistic side to Ali that people have swept under the rug, which popped up more often than has been assumed?

A: That wasn’t the only slap. This particular dynamic in their relationship was been written about elsewhere, not just in my book or in the work of George Plimpton. Bundini’s son shared some of these stories with me as well. The best way to understand it is to think of Ali and Bundini as brothers. Brothers fight. Khalilah compared the dynamic to that of Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn. Ali and Bundini argued quite often. They didn’t always get along or see eye-to-eye on important issues. No question. Those disputes sometimes became physical. I don’t think of Muhammad Ali as sadistic or as a bully. He was human. Humans make mistakes. Brothers fight. Brothers make up. Their love for each other was genuine. It was real.

Q: Outside looking in, did “Bundini” make the right call staying in that lane, as supporter of the top dog? Seems like he could have built up his own thing, as a cornerman, yes? Or was his constitution better suited as one who helped anchor a foundation, not a foundation in itself?

A: Bundini did, on occasion, venture outside of Ali’s world. Let’s not forget, he was featured in six Hollywood movies. (See clip from Bundini in “Shaft,” below.)

He was a recurring character in the Shaft movie franchise. He served as a chief second to James “Quick” Tillis. (NOTE: After the fight ends, NBC rolls corner footage from the bout, much of it starring Bundini.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CagkTFdr-P4

He owned a night club in Manhattan called “Bundini’s World.” But, to answer your question, yes. When Ali’s legendary career came to an end, Bundini struggled to reinvent himself. Much of his adult life was dedicated to serving Ali. I once had this exact same conversation with Drew Brown III. He pointed out the long history of trainers (and Ali team members) turned boxing analysts, think Ferdie Pacheco, Teddy Atlas, and Emanuel Steward. Drew and I both agree that listening to Bundini call fights would have been more fun than watching them. It’s a shame that Bundini didn’t get that opportunity.

Q: And lastly, when you ponder the lowercase legend that is Bundini, do you think within a context of the differences between then, and now? Do you find yourself wondering how Bundini plopped down in 2020, at his peak, would do? Or do you simply luxuriate in that block of time, treat it like the majestic contents of a time capsule, the likes of which we’ll never see again?

A: Tim Witherspoon, who I interviewed for the book, probably said it best. There has never been anyone like Bundini and there will never be another one like him ever again. It’s that simple. He was a true American original. Not even the most talented screenwriters in Hollywood could invent a character like him.