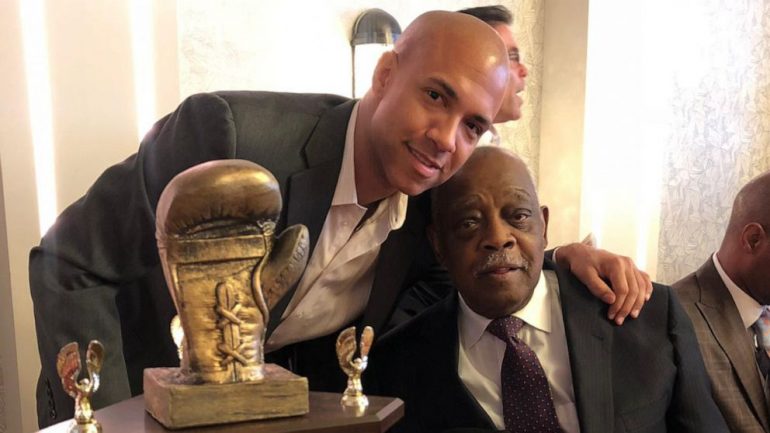

Adam Glenn proudly carries his legendary father Jimmy’s legacy into the boxing realm

Adam Glenn had an early realization who his father was. Once Jimmy Glenn’s head filled the TV screen, three-year-old Adam peered up and his eyes widened. He would move his cherub legs quickly across the parlor floor, press his face sideways up against the TV screen, stretch his tiny arms as far as he could diagonally and give his dad a virtual hug.

Jimmy Glenn may have been thousands of miles away, working the corner of an important bout on USA Network’s Tuesday Night Fights, though his baby son thought he felt it. In many ways, Jimmy probably did.

To the world, Jimmy Glenn was a legendary boxing figure as a longtime trainer, cut man and owner of the famous “Jimmy’s Corner,” the favorite watering hole near Times Square adorned with boxing memorabilia.

To Adam, Jimmy was “dad,” a giant of a man who would hip carry Adam into the Times Square Gym on 42nd Street every Saturday morning and whom he emulated, down to the penchant of chewing on straws.

On Thursday, May 7, 2020, Jimmy’s sudden death at the age of 89 due to COVID-19 complications not only struck those near and dear to him in the boxing world—it struck the world. The man whose great grandparents were slaves and whose grandfather was a sharecropper in South Carolina was memorialized by news outlet from CNN and ABC news to RingTV.com. Jimmy knew everybody from Frank Sinatra to Muhammad Ali. Important people thought Jimmy was important.

That’s the impact Jimmy had.

It obviously went far, far deeper to Jimmy’s youngest of seven children, Adam, now 40 and a Harvard law school graduate who owns his dad’s iconic bar. What’s more is that strong, visceral connection to his father’s love, boxing, has been passed on to Adam, who owns and runs the Times Square Boxing managerial company and the BXNGTV.com streaming service.

He manages Jeremy Hill (15-1, 10 knockouts), who will be fighting tonight at Philadelphia’s 2300 Arena against Nahir Albright for the NABA lightweight title, super middleweights Du-Shane Crooks (15-2, 8 KOs) and Sean Hemphill (12-0, 7 KOs) and junior welterweight Steven Galeano (7-0, 6 KOs).

“I miss him, I miss my dad every day, I miss him the most when one of my fighters wins and I can’t call him to tell him how the fight went, or when I have a big fight coming up or a big fight in Vegas, and we can’t go together,” Adam said. “Those are the moments when I miss my dad the most. It’s human nature, I think, that you miss loved ones when things are bad and you need someone to talk to. I miss my parents the most when things are good.”

Adam spent his entire life with people coming up to him that he never met before telling him they were his brother. Adam would cringe, then they would explain that Jimmy was like a father to them. They were old boxers Jimmy once worked with, or a kid Jimmy once helped. As Adam got older, he found his father had a way to open his heart to everyone. Adam worked in Jimmy’s Corner since he was 3. He would push buckets of ice around, and it would take him 20 minutes to fill a bucket and drag it to the foot of the steps. Adam would then yell for Jimmy, “Daddy, the ice is ready,” and Jimmy would walk down, pick up the bucket and take it to the bar.

“Sometimes, my father helped someone else because they needed it, and I try to have some of what my dad had, I try to be open and good-hearted and take care of people,” Adam said. “I was a kid when people would tell they were my brother and I didn’t understand. I wanted my dad to myself and I would tell these people, ‘He’s not your dad, he’s my dad’ (laughs).

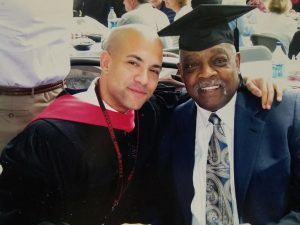

Six of Jimmy Glenn’s seven children are college graduates, including his youngest, Adam, a Harvard law school grad now following in his famous father’s footsteps into the boxing world.

“I used to think my dad can’t love everybody. That’s when you’re young. You want your father’s attention all to yourself. That obviously changed as I got older and I began to appreciate and realize that my dad had enough room to love everyone. I also knew no one was more important to him in the world than his kids.”

Six of Jimmy’s seven children are college graduates, while Jimmy went as far as the seventh grade. It always gnawed at Jimmy that he didn’t further his education, though in his times, he had to work to help his family. So, his children would have no choice but to get an education. Adam is the only child of Swietlana Garbarska, Jimmy’s second wife, a Jewish woman of Polish descent who came from a highly-educated family. Swietlana’s father, Adam’s maternal grandfather, was a college professor.

“The day I got into Harvard law school and the day I graduated, for my dad, he knew Harvard graduates, but it was a very special moment that one of them was his son,” Adam recalled. “I just remember my parents smiling the whole day I graduated. He was so proud, because he didn’t get a chance to go to school himself. I’m proud with what I’ve done, but I would take my dad any day over anyone I met at Harvard or walking down the street.

“I’m lucky, because my parents were the two smartest people I ever met in my life.”

Jimmy was an old-school outlier in many ways. He was the trainer other trainers sought out for advice. He never chased the money; he never undermined another cut man or another trainer to get to someone else’s fighter. It was an unbending decency rarely seen in boxing then, or now.

Adam Glenn is making inroads managing lightweight Jeremy Hill, pictured here with trainer Toby Wattigney.

Where some sons run from the considerable shadows their famous fathers cast, Adam runs to Jimmy’s. Jimmy is not in the International Boxing Hall of Fame, though he should be.

It’s a push Adam is advocating.

“My dad did everything, as a cut man, as a trainer, the impact he’s had on the sport makes him a Hall of Famer,” Adam said. “How many people can you think of knew every heavyweight champion from 1940, and sparred with Sugar Ray Robinson when he was a teenager, and once fought Floyd Patterson and was in camp with Muhammad Ali.

“My father should be in the Hall of Fame. I don’t think there are any questions about it.”

Jimmy could change the temperature of an entire room with a look. He used to have a mantra: “Give me a shot, I’ll make it.”

“I can still hear my dad saying that,” recalled Adam, whose mother died in 2015 from lung cancer. “I miss both my parents. Every day I hope the things I do will make my father proud. My parents are the voices that live in my head. To live a life like my father did, coming from where he came from, you have to be special.

“To me, my father was smarter than all of the educated people that I met. He always possessed a different kind of knowledge most people don’t have. There were people that didn’t like my dad, but they still respected him. No one could say my father lied to them, no one can say my dad cheated them, no one can say my dad did anything dishonest to them.

“My dad might not have done what they wanted him to do, but he always did what he said he was going to do. Boxing pays to be dishonest. It pays to be back-stabbing and to sell yourself over others. You see it in the boxing culture today where trainers steal fighters, and it’s something my dad wouldn’t do.

“All of my fighters are coming along, and my dad met all of them. It’s been a tough year from a boxing and life standpoint, but I can take joy in doing a lot of the same things he did. I would like to one day say that I’m the best boxing manager in the world, but my accomplishments don’t meet that. What I can say is I love and care about every one of my fighters, and being able to help them, like my father helped so many others. I can also say that I’m Jimmy Glenn and Swietlana Garbarska’s son and living up to that is what makes me proudest.”

Joseph Santoliquito is an award-winning sportswriter who has been working for Ring Magazine/RingTV.com since October 1997 and is the president of the Boxing Writers Association of America. He can be followed on twitter @JSantoliquito.

READ THE LATEST ISSUE OF THE RING FOR FREE VIA THE NEW APP NOW. SUBSCRIBE NOW TO ACCESS MORE THAN 10 YEARS OF BACK ISSUES.