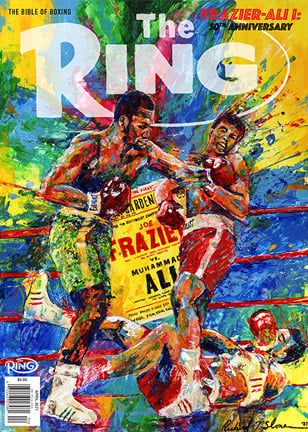

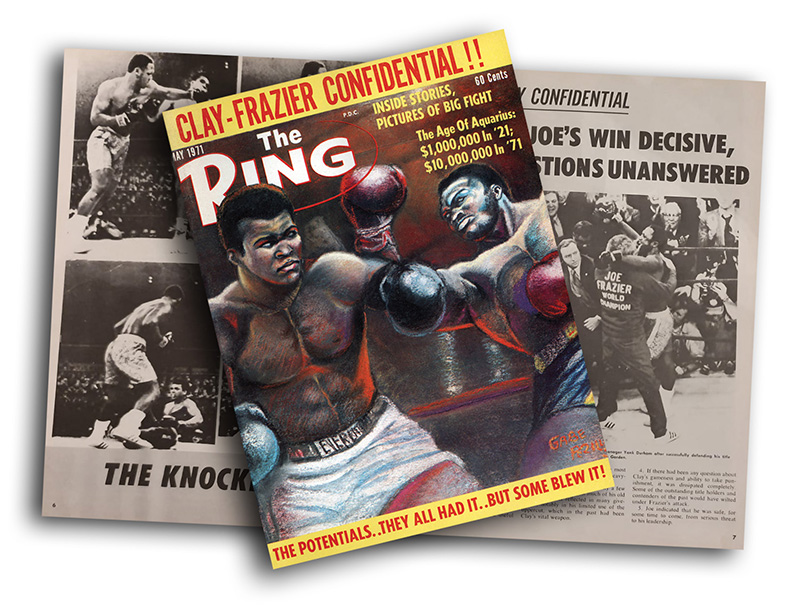

FRAZIER-CLAY CONFIDENTIAL

This feature originally appeared in the May 1971 issue of The Ring Magazine.

Editor’s note: Some of the author’s language and views may be considered offensive. In the interest of historical integrity, we did not remove the author’s original words from the story. We present this archival material as it was originally published (including the title of the article), in part, to document the perspectives, issues and social context of the times, which include the attitudes and opinions of the people who covered the fights.

THOUGH JOE’S WIN DECISIVE, MANY QUESTIONS UNANSWERED

In the aftermath of Joe Frazier’s emphatic victory over Cassius Clay by unanimous decisions of referee Arthur Mercante and judges Bill Recht and Artie Aidala, after a frenetic 15-round battle before 20,455 spectators in New York’s Madison Square Garden, quite a few questions and quite a few established facts present themselves.

The most interesting question is this: Could Clay, at his peak four years ago, have escaped defeat, which was clinched by a left hook which decked the Muslim in the 15th round?

Clay threw a lot of punches, but they were mostly for show and at no time had Frazier in danger.

Clay threw a lot of punches, but they were mostly for show and at no time had Frazier in danger.

Why did Frazier, after punishing his man with body blows in the first four rounds, switch to the head?

When this question was put to Yancey Durham, the champion’s trainer-manager, he replied, “Because I told him to.” When Yank was pressed for more explicit information, he refused to extend his remarks.

Did Frazier’s efforts realize his ultimate potential against Clay? In the light of what Joe found out about Cassius, would the titleholder be expected to stop his man in a second meeting?

Is there to be a return engagement, and where?

Did the fight, with its $150 ringside admission price, the $5,000,000 guaranteed, share and share alike, to the contestants, come up to expectations and justify the attendant hysteria?

Reviewing the facts established by the 45 minutes of action, we find these outstanding:

Clay’s unorthodox conduct right through the fight, with the exception of the 11th and 15th rounds, in which he was in serious danger of a knockout, established him as the standout actor in heavyweight history. He made John Barrymore at his best look and sound like a busher of the footlights.

Muhammad set himself up as the master of in-ring insult, and effort to turn derision, in spite of pain, into a useful weapon. In that regard he was the most active perpetrator in the history of heavyweight glove fighting.

It was easy to see, after only a few rounds, that Clay had lost much of his old speed. This was reflected in many giveaways, notably in his limited use of the uppercut, which in the past had been Clay’s vital weapon.

If there had been any question about Clay’s gameness and ability to take punishment, it was dissipated completely. Some of the outstanding titleholders and contenders of the past would have wilted under Frazier’s attack.

Joe indicated that he was safe, for some time to come, from serious threat to his leadership. Eliminate Clay and the only current heavyweight who might draw with Frazier in the future is George Foreman, who is being nursed along carefully with a title shot in view once Muhammad is erased from the scene, either by another defeat by Frazier or a Supreme Court verdict sending him to a Federal penitentiary for anywhere from two to five years for refusal to respect an Army draft.

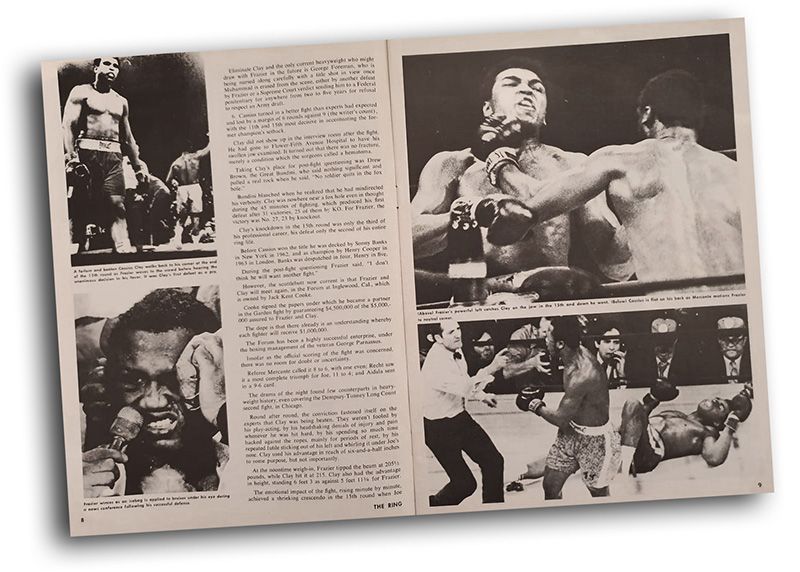

Cassius turned in a better fight than experts had expected and lost by a margin of six rounds against nine (the writer’s count), with the 11th and 15th most decisive in accentuating the former champion’s setback.

***

Clay did not show up in the interview room after the fight. He had gone to Flower-Fifth Avenue Hospital to have his swollen jaw examined. It turned out that there was no fracture, merely a condition which the surgeons called a hematoma.

Taking Clay’s place for post-fight questioning was Drew Brown, the Great Bundini, who said nothing significant and pulled a real rock when he said, “No soldier quits in the fox hole.”

Bundini blanched when he realized that he had misdirected his verbosity. Clay was nowhere near a fox hole even in thought during the 45 minutes of fighting which produced his first defeat after 31 victories, 25 of them by KO. For Frazier, the victory was No. 27, 23 by knockout.

Clay’s knockdown in the 15th round was only the third of his professional career, his defeat only the second of his entire ring life. [Editor’s note: The article is reprinted here in its original form, but it should be said that Ali had at least five losses as an amateur.]

Clay’s knockdown in the 15th round was only the third of his professional career, his defeat only the second of his entire ring life. [Editor’s note: The article is reprinted here in its original form, but it should be said that Ali had at least five losses as an amateur.]

Before Cassius won the title, he was decked by Sonny Banks in New York in 1962 and by Henry Cooper in 1963 in London. Banks was dispatched in four, Henry in five.

During the post-fight questioning, Frazier said, “I don’t think he will want another fight.”

However, the scuttlebutt now current is that Frazier and Clay will meet again, in the Forum at Inglewood, Cal., which is owned by Jack Kent Cooke.

Cooke signed the papers under which he became a partner in the Garden fight by guaranteeing $4,500,000 of the $5,000,000 assured to Frazier and Clay.

The dope is that there already is an understanding whereby each fighter will receive $1,000,000.

The Forum has been a highly successful enterprise, under the boxing management of the veteran George Parnassus.

Insofar as the official scoring of the fight was concerned, there was no room for doubt or uncertainty.

Referee Mercante called it 8 to 6, with one even; Recht saw it a most complete triumph for Joe, 11 to 4; and Aidala sent in a 9-6 card.

The drama of the night found few counterparts in heavyweight history, even covering the Dempsey-Tunney Long Count second fight, in Chicago.

Round after round, the conviction fastened itself on the experts that Clay was being beaten. They weren’t fooled by his play-acting, by his headshaking denials of injury and pain whenever he was hit hard, by his spending so much time backed against the ropes, mainly for periods of rest, by his repeated futile sticking out of his left and whirling it under Joe’s nose. Clay used his advantage in reach of six-and-a-half inches to some purpose, but not importantly.

At the noontime weigh-in, Frazier tipped the beam at 205½ pounds, while Clay hit it at 215. Clay also had the advantage in height, standing 6 feet 3 as against 5 feet 11¼ for Frazier.

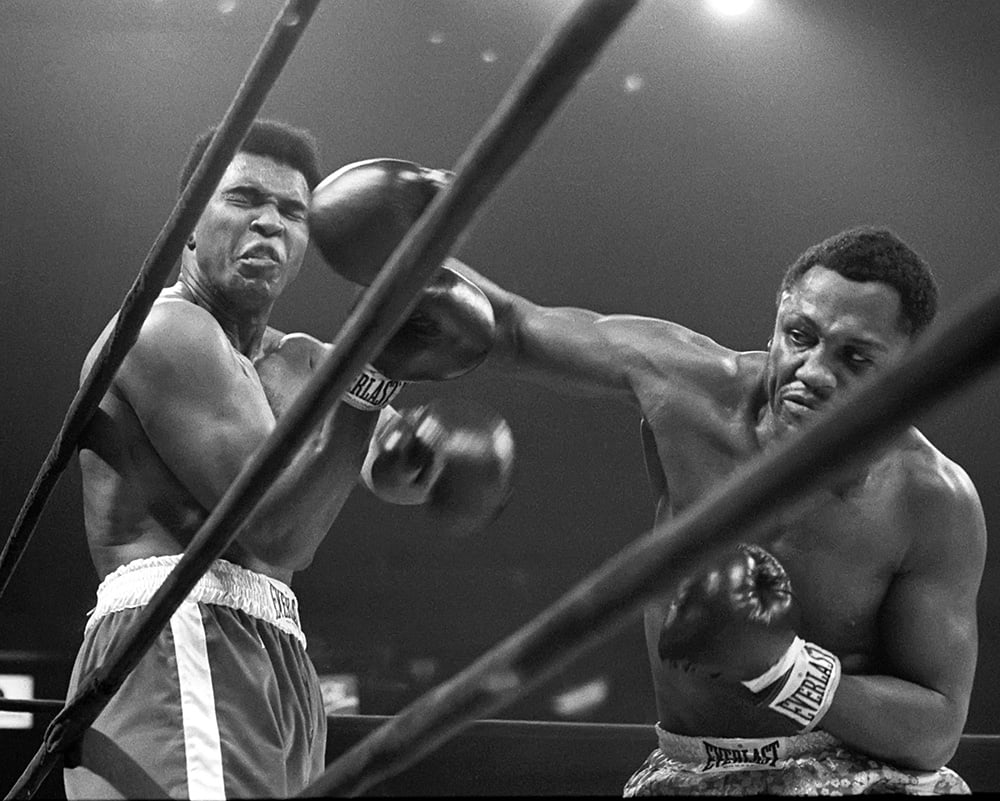

Frazier, the quintessential left hooker, landed his fair share of rights during the showdown. (Photo by David Hume Kennerly/Bettmann/Corbis via Getty Images)

The emotional impact of the fight, rising minute by minute, achieved a shrieking crescendo in the 15th round when Joe unleashed a terrific left hook which found its target on Clay’s right cheek and sent him sprawling on his back.

Down went Cassius, amid excitement rarely matched in heavyweight title history.

The general supposition was that Clay had been knocked out. But he jumped up quickly and, summoning whatever faculties still were functioning, he put on a flurry. Soon, the bell!

Referee Mercante handled the exciting situation with coolness and skill, in sharp contrast to the 15th round situation not so long ago in the Garden ring, when Clay decked Bonavena thrice.

How New York was thrown into hysterical expenditure to make the $1,352,952 gate at the Garden, by the unprecedented harvests of the scalpers and the dealers in counterfeit tickets, by the dramatic response of the spectators, by the bizarre accoutrements of so many of the spectators, is a story yet to be told.

When it was all over, there was wholehearted appreciation of Joe Frazier, of Philadelphia, age 27, not so many years ago a $75-a-week worker in an abattoir.

It was a bad night for the Clays. Not only was Cassius beaten, but Clay’s younger brother, Rudy, was a loser in a six-rounder with Britain’s Doc McAlinden.