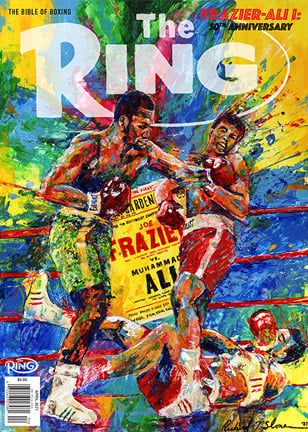

THE WORLD AS SEEN FROM THE CENTER OF THE FRAZIER-ALI STORM

Before 1971, there was 1910 and 1938. Years when heavyweight rumbles shook the earth. Morphed into visceral symbols of political and cultural unrest. Reaching a crescendo with Ali-Frazier, two undefeated champions. I had visions of Eskimos watching them in igloos, natives on remote Polynesian islands, cellular life on Mars.

1910. Jack Johnson, the first Black heavyweight champion, challenged by Jim Jeffries, a long-retired champ answering the pleas of distraught fans to make everything right, i.e., White, again. It was in Reno and it was not to be. Johnson taunted “The Great White Hope” for 14 rounds and stopped him in the 15th. America’s sore-loser racists then did what they do, rioted, in cities from sea to shining sea. Twenty or so Black people were killed. The Feds added insult by contriving a law that charged Johnson with transporting (White) women across state lines for illicit purposes. Johnson, a master counterpuncher, promptly transported himself to Paris, where he spent much of the next decade before retiring.

(Photo by John Shearer/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images)

Sidebar. In 1970, not ’71, Ali emerged from a three-and-a-half-year state-sponsored retirement on account of he refused to be drafted during the controversial war in Vietnam. (The Supreme Court would vindicate him.) A couple nights before he beat Jerry Quarry in Atlanta, we found ourselves standing outside a movie theater after watching a documentary about … Jack … Johnson. I was then one of the young media dogs who barked and wagged at Ali’s parade of amazements, representing the Philadelphia Daily News, where I was sports editor and columnist.

“You think I’M crazy?” Ali said to my bemused self. “Jack Johnson was REALLY crazy.” Translated: Ali did not mess with White women.

1938 is personal. After dinner, my father told my 7-year-old self that I could stay up late for the broadcast of the Schmeling-Louis war of the worlds. At nearby Yankee Stadium, my favorite place. I sensed something cosmic was happening, because I had seen headlines in newspapers and heard fevered reports on the radio. Though Schmeling wasn’t a Hitler cultist, he was cast as the evil German, from a country we had fought in World War I and were seemingly headed for a dreaded rematch. Joe Louis was our guy, the good guy, America. He had been the first Black fighter to fight for the title since, and because of, Jack Johnson. I heard the mad Hitler on shortwave radio as my mother moaned. His pro-Aryan rants, interpreted by our foreign correspondents, sounded, in his native tongue, like live machine-gun bullets from across the ocean. It was bigger than a big fight, like Johnson-Jeffries before and Ali-Frazier after.

As we all know, Louis demolished Schmeling and deflated Hitler in one round. Joe Louis would become our first Black hero. I like to say that he ended the fight so fast because he didn’t want me to stay up too late.

Cut to 1971 and the long-awaited showdown between two great fighters with contrasting styles in and out of the ring, during a national nervous breakdown. President John and brother Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King were murdered in the ’60s, and President Nixon would soon be booted out of office. Then an anti-war movement, civil rights and pro-women movements, with uplifting or maddening marches and protests, and the equally serious currents of psychedelic drugs, new young music, free love, crazy clothing. Changes “blowin’ in the wind” that divided us. Liberals rooted for Ali, conservatives rooted against Ali or for Frazier, as though their lives and their children’s futures depended on it. I went to a Beatles press conference once for the hell of it.

Frazier and his trainer-manager, Yank Durham, check the scales on fight day.

I knew and loved Ali and Joe both. Maybe I adored Ali a little more because of his rebellious spirit and unrivaled showmanship. Early on, I spent a couple hours with him at his home in Miami. And left laughing. I knew Joe Frazier in Philadelphia, where he had moved from a farm in South Carolina to develop his career. After he won gold in Tokyo in 1964, he had to stay on his job in a slaughterhouse to support his young family. A group of civic leaders, lawyers and ministers and such formed a company, Cloverlay, a variation of a group that had backed Ali in Louisville, so Joe could be a full-time professional. They sold 80 shares at $250, a total of $20,000. I bought one of them – a week’s salary – as a stunt. I could then write about him as “my fighter.” Eight months later, I had to sell the share, already valued at $2,000, because I needed to move into an apartment in New York for my new job at the Post. Joe never failed to remind me that I sold him short. In two years, a share was worth $14,000.

I was sure that Frazier had at least won what I call the drama of a fight. … But I was among the few astigmatic dunces in the room who scored it for Ali.

The fight, the big-bigger-biggest one, starts in memory when I had a rendezvous with Jim Brown, the football god who had gone into acting and was a pal and fan of Ali. It might have been days before the opening bell. He asked me what I thought. I said I leaned toward Frazier because I didn’t think Ali could be fully restored from those lost years. Brown nodded in agreement, but I wasn’t sure what he truly felt. My pre-fight column veered in another direction. I wrote that Frazier might have beaten Ali on his best day, but I had to pick Ali because I wanted him to win.

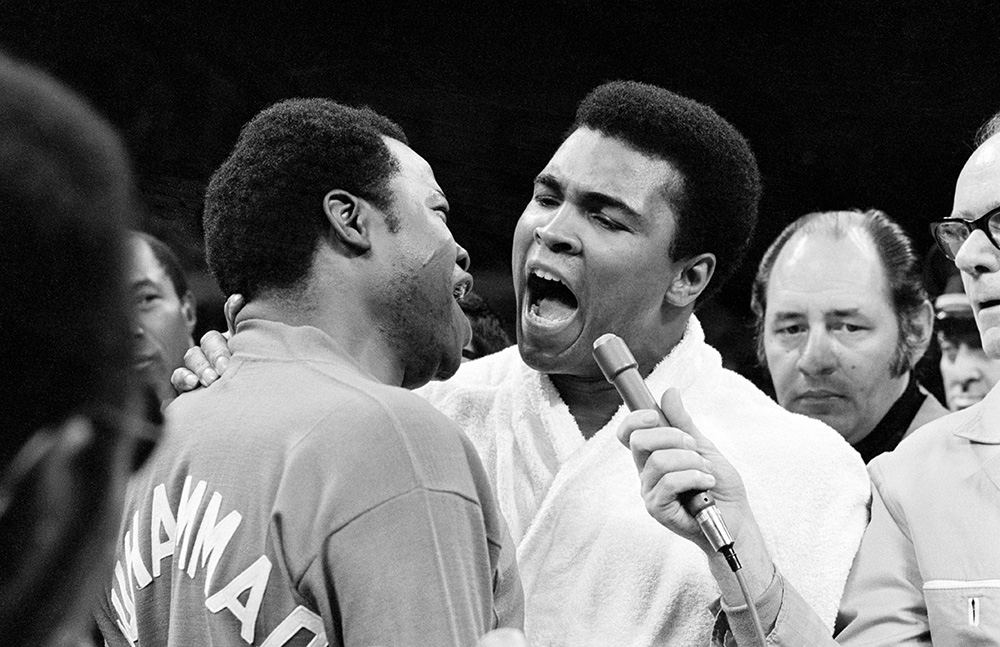

Ali and loquacious cohort Drew “Bundini” Brown ham it up at the weigh-in.

My takeaways on the night. The dark-suited tough guys on the floor, politicians and their lawyers, mobsters, and their dolls. The celebrities led famously by Frank Sinatra covering the event for Life magazine. The visceral roars, unlike anything I had ever heard anywhere, exploding down the canyons and through the history of Madison Square Garden, over and over and over, round after round. When Ali pranced and danced and mugged, I winced because I felt that establishment officials would not look kindly at his act. That could be the difference between winning or losing a close round. Frazier taking more clean shots, more punishment, than I had ever seen a fighter take, blood on his face, blood on the canvas. But still digging after Ali, landing hard left hooks in close. He started to pull away in the middle rounds, but in the ninth Ali rocked him again and again. Frazier closed the show with a knockdown in the 15th.

I was sure that Frazier had at least won what I call the drama of a fight. Landing punches that can be seen from the rafters on a star opponent who rarely if ever is abused. And, surely, he would get credit for aggression, “making the fight,” as they say. But I was among the few astigmatic dunces in the room who scored it for Ali.

The knockdown that shocked the world.

I had no quarrel with the result, assuming that emotion had distorted clarity. But over time I began to question myself again.

The next day’s Daily News, the largest-circulated newspaper in the country, had a provocative front page. On one side, Joe Frazier, his face a bloody pulp, with the headline: THE WINNER. On the other side Muhammad Ali, his face slightly distended but otherwise clear, with the headline: THE LOSER.

And then we would learn that Frazier spent more than a week in a Philadelphia hospital, recovering from bruising he took and the effort he gave.

And then way later, before Ali would decision Joe in the rematch and score a TKO in the third fight, which is widely regarded as the fiercest heavyweight fight ever, my colleague and friend Vic Ziegel, who had scored the first fight for Frazier, went into a studio to take the whole thing apart on film. Now I know you can no more take a fight apart punch-by-punch than you can break down an opera note-by-note. But here’s what we found, long before the punch-stat tool was invented:

In one round, Ali landed 19 clean punches to Frazier’s three, and one of the judges gave it to Frazier. Overall, Ali landed 180 or 190 clean punches to Frazier’s 90.

What the hell, the fight generated the highest expectations and exceeded them.

And conservatives were consoled that the future was not there yet. Insincerely, I hope they did not bet their houses on the rest of the trilogy.