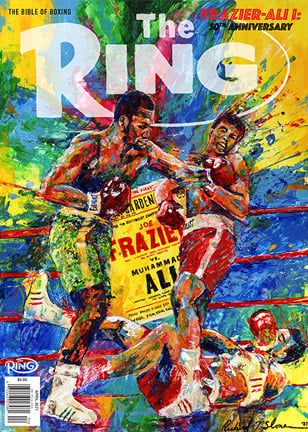

ONLY TWO FIGHTS IN HISTORY, JOHNSON VS. JEFFRIES AND LOUIS-SCHMELING II, CAN MATCH THE SOCIAL IMPACT OF FRAZIER’S SHOWDOWN WITH ALI, BUT ‘THE FIGHT OF THE CENTURY’ WAS AN EVEN MATCHUP AT THE HIGHEST LEVEL AND SMOKIN’ JOE WON

When he left the ring that night in 1971, Joe Frazier’s body language betrayed the enormity of what he’d just endured. He moved slowly down the aisle at Madison Square Garden, keeping a hand on his trainer, Yank Durham, for support. He’d won the fight, but his opponent, Muhammad Ali, had inflicted some severe punishment on him. Frazier’s face was so swollen that he refused to have his picture taken for several days, fearing people would think he’d actually lost. Add to this a lengthy hospital stay to deal with some serious post-fight health issues, followed by a 10-month sabbatical from the ring, and it seemed as if Frazier’s response to the grandest night of his boxing life was to turn invisible. Perhaps this was to be expected. Winning what was the biggest spectacle in boxing history was bound to leave a man depleted. He’d not won a mere boxing match. He’d won an American moment.

Frazier’s problem was that he’d beaten a man who was already a sort of living legend.

Noticeable during the bout’s immediate aftermath, however, was that the story being told was not Frazier’s, but Ali’s. The trio of ringside commentators – veteran broadcaster Don Dunphy, Oscar-winning actor Burt Lancaster and former light heavyweight champion Archie Moore – were overheard during the end credits of the closed-circuit transmission. Their discussion concentrated almost entirely on Ali’s bravery and the way he came back after being hurt. Dunphy finally offered some praise for the winner, probably just as Frazier was entering his dressing room in a state of near-collapse.

“Joe Frazier has just scored the biggest victory of his career,” Dunphy said. Then he added, with a matter-of-fact inflection, “Of anybody’s career.” Dunphy’s observation had merit, if only because he’d been calling fights for three decades and had been ringside for some classic events.

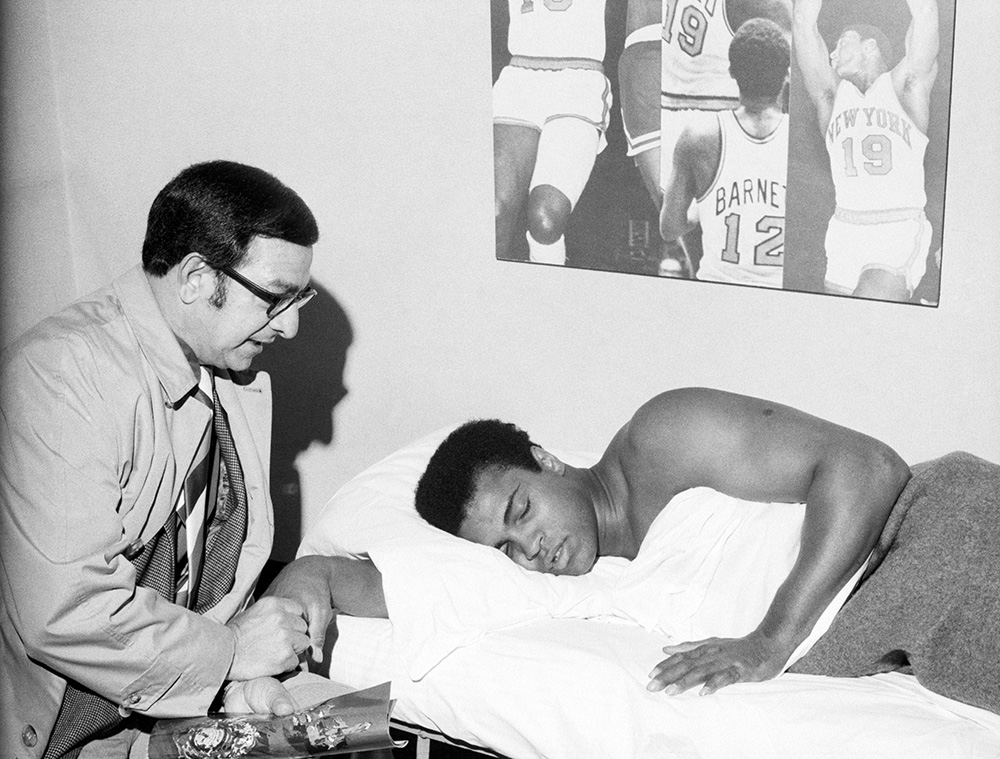

The weigh-in over, Ali, seen here with trainer Angelo Dundee, rested at The Garden until fight time.

It is reasonable to rate Frazier’s win over Ali as the greatest single victory in the annals of boxing. Red Smith of The New York Times, who had been writing about sports since the 1930s, described the fight as “the most hysterically ballyhooed promotion of all time,” what with two young, undefeated heavyweights, each with a legit claim to being champion, each with superior talents, squaring off for an unprecedented amount of money, with the drama beamed to theaters all around the globe, stretching the limits of the available technology; riots broke out in venues where the signal broke. Logically, the winner of the biggest fight should be acknowledged as having recorded history’s biggest win. Such arguments are difficult, though, and fruitless. All that is certain is that when it came to winning a contest of such import, only a few men had ever been in Frazier’s shoes.

READ Muhammad Ali: Global Icon

Joe Louis, for instance, in his 1938 bout with Max Schmeling, found himself not only defending the heavyweight title against the sole fighter who had beaten him at that point – Schmeling had knocked him out two years earlier – but was battling a German opponent just as the war in Europe was brewing. Louis destroyed Schmeling in one round and became a folk hero in the process. Of course, biographers have overplayed the war backdrop as if Louis were fighting Adolf Hitler himself, but it was a massive event, certainly the most discussed bout of the 1930s. Louis and Schmeling pulled more than 70,000 fans to Yankee Stadium while an estimated 100 million listened to the bout wherever radio signals could reach.

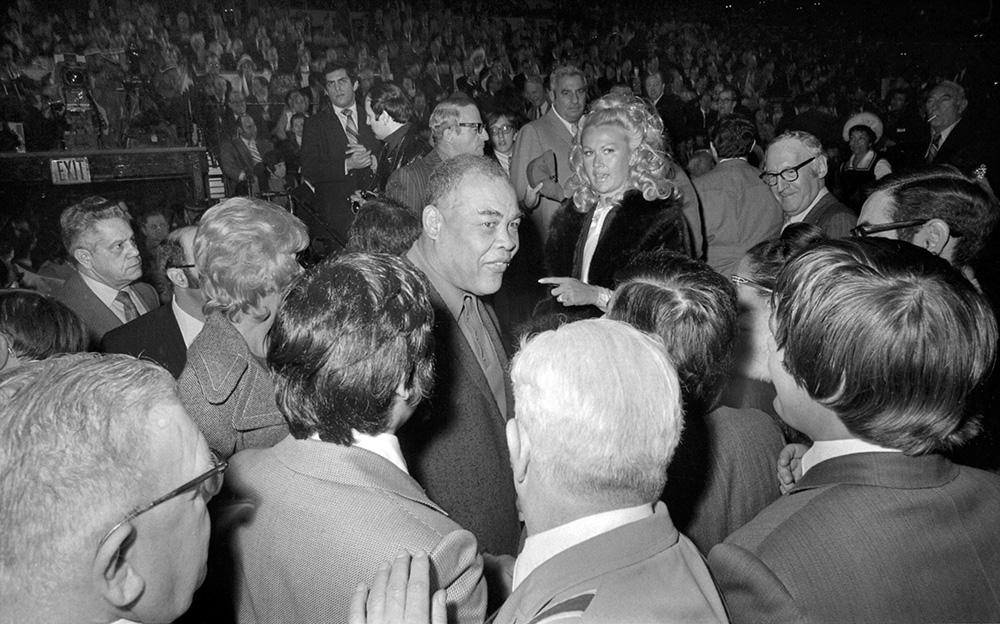

Legendary former champion Joe Louis was never going to miss The Fight.

Though the audience was restricted to a dusty, makeshift stadium in Reno, the 1910 fight between heavyweight champion Jack Johnson and James J. Jeffries surely felt as if something major was at stake. Jeffries’ backers had lured him out of retirement in hopes that he would level Johnson and strike a blow for White supremacy. Indeed, the bout attracted so much ugliness that more than two decades passed before another mixed-race bout would be held for the heavyweight title. Johnson stopped Jeffries in the 15th round and spent several days afterward enjoying one wild reception after another. The Ring’s founder, Nat Fleischer, actually accompanied Johnson on his train ride east from Reno and recalled the throngs of African Americans waiting at each station to get a glimpse of their hero. “When we reached New York,” Fleischer noted in his 1958 autobiography, 50 Years at Ringside, “the crowd was so dense the police had difficulty clearing a path for the homecoming party …” In the same memoir, Fleischer barely mentioned Louis-Schmeling II, which suggests how large the Johnson-Jeffries fight loomed in his memory.

A powerful social undercurrent also elevated the first Ali-Frazier bout into something far beyond boxing. Some would say that it lacked the sheer historical weight of Louis-Schmeling II or Johnson-Jeffries, but the contest was startling in the way it seemed to erupt out of the era’s political climate. Ali, the draft resister, so represented the radical left that Frazier became a de facto stand-in for the conservative crowd. Frazier couldn’t have cared less about such things; he was there to defend his title and make money. For that matter, conservatives were less interested in seeing Frazier win than to see Ali lose. Still, so strong was the fight’s political atmosphere that when theater critic Kenneth Tynan mentioned it in one of his published diaries, he described Ali’s defeat as a “belated epitaph of the Sixties,” and labeled Frazier as Richard Nixon’s “hatchet-man.”

READ: Mike Tyson looks back at 10 heavyweight champions before him (The Ring, Sept. 2020)

Linking Frazier to right-wing principles may sound odd, but much of the post-fight coverage was delivered with a countercultural bent. Many of the journalists who had supported Ali during his exile were decidedly left-leaning and looked at him as royalty, a fallen king without a domain. His personality, his place in the world, was simply too large to ignore, his tale too compelling. In comparison, Frazier seemed painfully old-fashioned, not a king but a mere fighter, as Norman Mailer described him, with the “face of a man who spent his days laboring in the pits.” The irony is that Frazier was cool – he spoke in a kind of musician’s patter, had a closet full of trendy clothes and even fronted a rock band in his free time – but to the press and the general public, he was about as interesting as a farmhand, still reeking from the slaughterhouses of his youth.

Frazier’s problem was that he’d beaten a man who was already a sort of living legend. The scenario was supposed to see Ali stand up to the government and then regain the heavyweight championship of which he’d been unjustly stripped. Ali had the liberals, the hippies, the war protesters and just about anyone under 30 on his side. The majority of Black fans were with him, too. The table was set for Ali to stick it to the U.S. government and everyone else on the wrong side of history. All he had to do was beat Frazier. Then Frazier swooped in with his left hook and ruined the story.

All that is certain is that when it came to winning a contest of such import, only a few men had ever been in Frazier’s shoes.

Granted, many had rooted against Ali – Scottish journalist Hugh McIlvanney claimed to have heard White American reporters shouting for Frazier to “Kill the sonofabitch” – but whatever satisfaction they took in his downfall was brief. Though humble in defeat, Ali eventually saw to it that Frazier’s win was downplayed. With the instincts of a seasoned spin doctor, Ali assured his followers that he’d deserved the decision, that the ringside judges were biased against him, and that it was clear who won simply by looking at Frazier’s face after the bout. Using only his tireless mouth, Ali dismantled Frazier’s achievement with the effectiveness of a wrecking ball. Most damning for Frazier was that a chunk of the population was swayed by Ali’s argument. “You saw the fight,” Frazier once said to columnist Jerry Izenberg. “You know I won. So what I got to do to convince everyone? What the hell I got to do?”

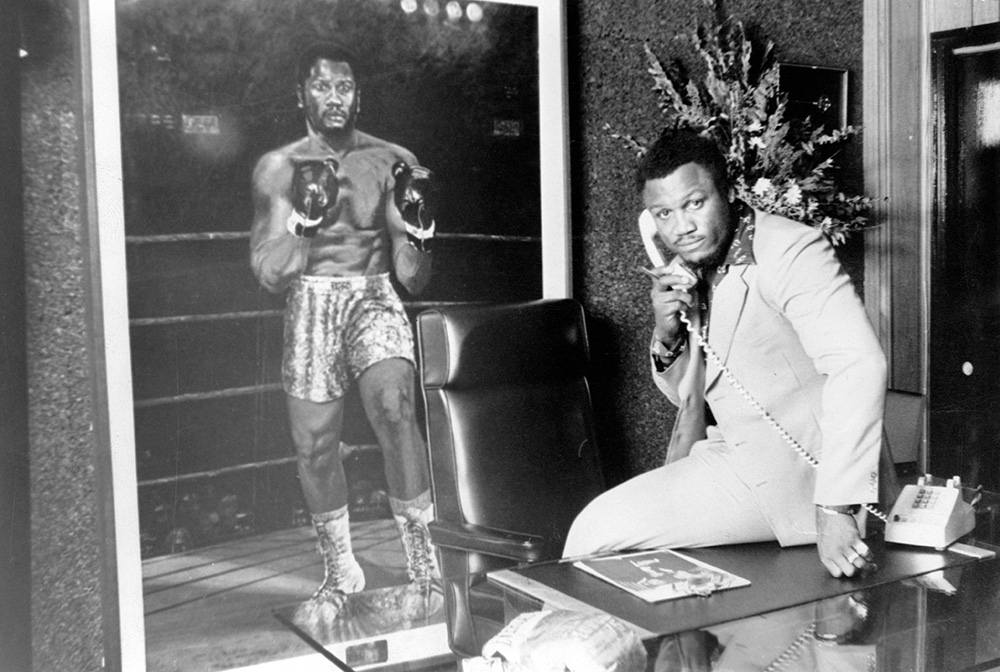

Frazier, seen here in 1972, was the champion, but he was still overshadowed by Ali.

In a way, Frazier’s win was so big that he could hardly live up to it. The best the press could say for him was that he was an “honest” and “hard-working” champion, words that seemed rubber-stamped into every story about him. Stranger still was how the status quo remained unchanged. Ali was everywhere, talking nonstop; Frazier, the quiet family man, remained in his shadow. It was as if Ali gained more from losing than Frazier did from winning.

Frazier found himself in the same light as Gene Tunney after his second victory over Jack Dempsey. By the time of that 1927 bout, Dempsey stood taller than ever in the minds of his fandom. He’d lost the heavyweight championship to Tunney the previous year but had been gallant in defeat and now seemed destined to regain the laurels. He even knocked Tunney to the canvas for the legendary “long count,” proof that he still had a champion’s punch, if not the sense to go to a neutral corner. But Tunney rose, won the decision and spoiled the fantasy. Tunney understood Dempsey’s hold on the nation, so he was civil after the bout, always giving Dempsey credit and respect. Tunney, however, didn’t have to deal with the constant affronts that Frazier suffered from Ali.

Also unlike Tunney, who retired after one more bout, Frazier kept fighting. His return to boxing revealed a slightly different “Smokin’ Joe,” one who had lost some spark; he’d become a chubby, almost clumsy version of his old self, as if beating Ali had required the blowing of irreplaceable fuses. Gentleman Jim Corbett, the great champion of the early gloved era, once observed that all fighters have a night where they box better than they ever have and ever will again. He could’ve been speaking of Frazier, who had peaked majestically on March 8, 1971, but never quite regained that diabolical form, that mix of determination and hostility.

The fight that had captured the world’s imagination was eventually revised and remade as the opening act of a much larger narrative, one that climaxed more than four years later in the Philippines, with Frazier’s corner stopping the action after the 14th round. Once Ali emerged as the last man standing, the instantly fabled “Thrilla in Manila” appeared to supersede the first Ali-Frazier bout, as if he who wins last wins best. It also appeared that the end of the Vietnam War had somehow diminished the first bout’s magnitude. When The Ring’s editors compiled a coffee table book in 1981 called The Great Fights, the Manila bout received an entire chapter, while the first fight was given only a fleeting mention. During the 1990s and 2000s, as Ali’s status grew and morphed into something like sainthood, Frazier was reduced to being a supporting player in the saga. As William Nack of Sports Illustrated put it, Frazier became “a dragonfly embedded in the amber of Ali’s life and times.”

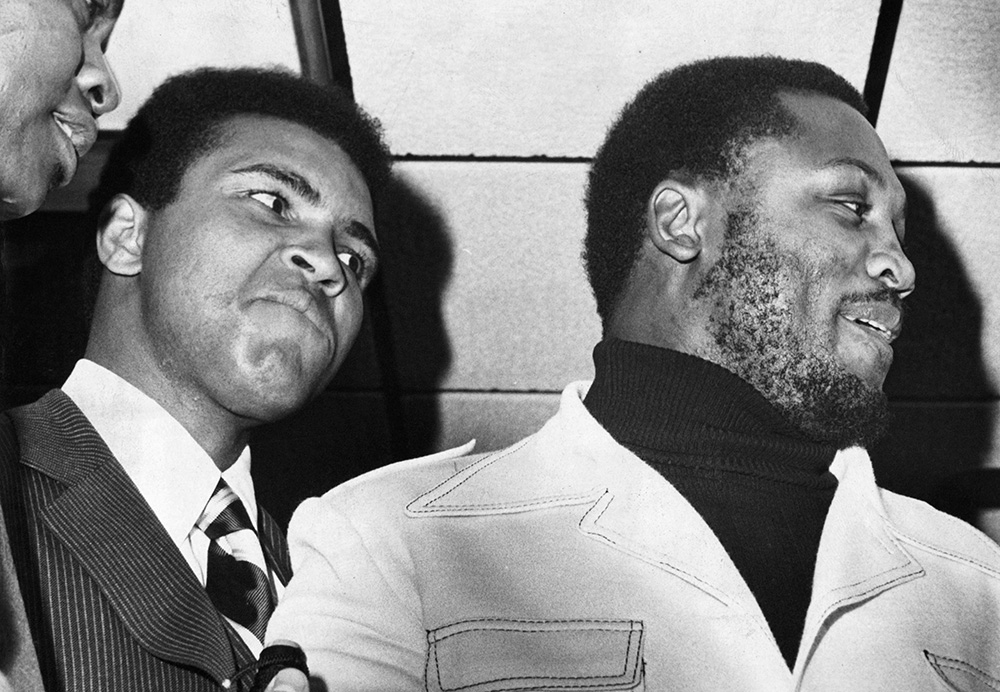

A brief moment of levity ahead of the heated 1974 rematch.

Frazier’s sourness increased each year, in equal measure to Ali’s growth as an international symbol. However, his resentment toward Ali cost him. Ali’s failing health had made him a pitiable figure, and Frazier’s caustic comments toward his old rival were poorly timed. There were inklings, though, that the two men reached an understanding. In 2011, on the 40th anniversary of the first bout, and only seven months before his death, a mellow Frazier told the Associated Press that beating Ali had been “the greatest thing that ever happened in my life.”

But was it boxing’s biggest win? Yes, more than likely. Who’d argue against it?

In the half-century since, there have been some major upsets and a few victories that, with some generosity, might even be considered important. There have been extreme moneymakers, while advances in technology have allowed fights to be viewed by more people than ever. There have been some excellent fighters and performances that were spellbinding. But that first Ali-Frazier bout made everything else in the country stop cold for an hour. Even people who cared nothing for boxing were tuning in to their local radio stations that night, hoping for some updates, just to be part of it. With such electricity in the air, and an opponent who had seemed unconquerable, Frazier set about his mission with blinders on. He had to be aware of the pressure that was on him, but he smashed through it all. He was magnificent.

Consider this: While it’s true that Ali was far from his best in 1971, he was still good enough to beat most any other heavyweight in the world. Frazier’s win was hard-earned, one of the most rugged and difficult title defenses a heavyweight champion had ever made to keep his crown. Also, if Ali had won, it would’ve been heralded as the sports story of the decade and, certainly, the biggest win ever in the fight business. The noise would’ve reverberated for months. And so it should have for Frazier.

His failure to fascinate the masses shouldn’t take away from Frazier’s victory– his effort of 50 years ago remains a masterpiece of aggression – though it explains why he was often bitter. Frazier’s role in history was not as a great or brilliant pugilist, but merely as Ali’s bête noir, the storm through which Ali had to walk. Still, it should never be forgotten that when the whole world was watching, at a time when nothing else on the planet seemed to matter, the hand raised at the end of boxing’s biggest night belonged to Joe Frazier. A simple fighting man had beaten the icon.