Jabs and Straight Writes

I Was at Ali-Frazier I . . . and Two Postscripts Decades Later

In early 1971, I read that Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier had signed to fight at Madison Square Garden. I’d graduated from Columbia Law School the year before and was clerking for a federal judge prior to a five-year stint as a litigator on Wall Street. The United States Supreme Court had yet to rule on Ali’s appeal of his 1967 conviction for refusing induction into the United States Army. But a recent federal court ruling had allowed him to return to the ring while his appeal was pending.

It was clear that Ali-Frazier would be a memorable event – two great fighters, each one undefeated with a legitimate claim to the heavyweight championship of the world. Just as clearly, it would transcend sports.

Tickets for the fight were priced from $20 to $150. The day they went on sale, I bought two mezzanine seats at $20 apiece. On fight night, scalpers were getting 10 times those numbers.

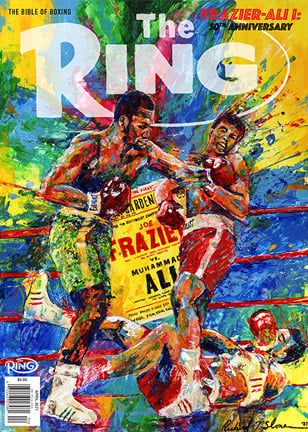

I went to the fight with a friend. Entering the Garden, I bought an official program that had a LeRoy Neiman painting of Ali and Frazier on the cover. The arena was jammed. There was electricity in the air. Superstars who were accustomed to sitting in the front row on camera were 15 rows from ringside and happy to be there. Frank Sinatra finagled a press credential by agreeing to photograph the fight for Life magazine. Thousands of fans stood outside the arena just to watch the celebrities come in.

None of the preliminary fights were slated for more than six rounds. The most notable undercard bout featured Ali’s brother, Rahaman, against Danny McAlinden.

Rahaman had fought on the undercard of both Ali-Liston fights and Ali versus Oscar Bonavena. His record stood at seven wins and no losses with three knockouts. McAlinden was a heavyweight born in Northern Ireland who had moved to England. His record was 14-1-2 with 13 KOs.

Fights in New York were scored at that time on a round-by-round basis, not on points. McAlinden won a 4-2, 3-2-1, 3-3 majority decision.

As the night wore on, the tension grew.

Finally, it was time.

“I’ve covered sports for a half-century,” Jerry Izenberg reminisced years later. “I’ve been to every kind of championship and seen every great athlete of the past 50 years. No moment I’ve ever seen had the electricity of Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier coming down the aisle and entering the ring that night.”

People forget how young Ali and Frazier were then. Muhammad was 29, Joe only 27. But even though some of Ali’s greatest ring triumphs lay in the future, he was already growing old as a fighter. So was Joe.

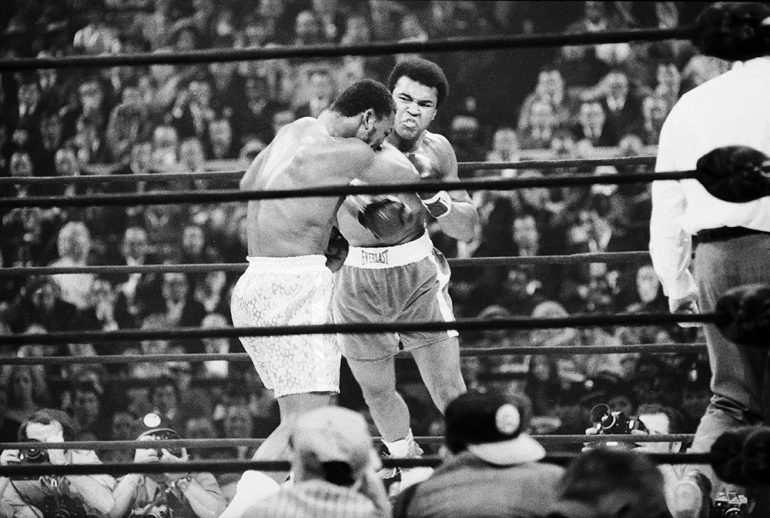

The fight was close in the early rounds. The crowd was evenly divided. But as the night wore on, Frazier’s fans had more reason to cheer.

I left Madison Square Garden that night feeling depressed but knowing that I had witnessed something historic.

I remember Ali going to the ropes, beckoning Frazier in. I remember Round 11 when Joe wobbled Muhammad with a big left hook. And most painfully, I remember the 15th round when Frazier hit Ali as hard as a man can be hit and Muhammad went down. At that point, the fight was lost. My hope was that Ali would be able to finish with dignity on his feet. He did, although the decision went against him by an 11-4, 9-6, 8-6-1 margin.

Ali-Frazier was Muhammad’s first “superfight.” Against Sonny Liston in 1964, Cassius Clay had been widely perceived as nothing more than a kid coming to get beaten up. Ali-Liston II in 1965 drew only 2,000 paying fans. Now, when it mattered most and the world truly cared, “The Greatest” had failed.

I left Madison Square Garden that night feeling depressed but knowing that I had witnessed something historic.

Fast-forward 20 years to April 14, 1991. I’d left the practice of law to write and, by a twist of fate, had become Ali’s biographer. The manuscript for Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times was complete and would be published in several months. I was with Ali at a hotel in Philadelphia (Frazier’s hometown) for a black-tie gala celebrating the 20th anniversary of the first Ali-Frazier fight.

Late that afternoon, I went to the dining room to look around. The hotel staff was setting up. Howard Bingham (Ali’s best friend and personal photographer) was sitting on the edge of a table, talking with a man who was wearing a tuxedo and a green-black-and-red kufi.

“This is someone you should meet,” Howard told me.

Because the man was sitting, I didn’t realize how big he was.

“I’m Jim,” the man said.

He stood up and extended his hand.

And the realization hit.

“Jim Brown,” I blurted out.

“No,” he corrected. “Just Jim.”

I’d met Frazier 28 months earlier at the Sahara Hotel in Las Vegas. Two days of taping were underway at the time for a documentary entitled Champions Forever that would feature Ali, Joe, George Foreman, Ken Norton and Larry Holmes. I’d been there with Muhammad to conduct interviews as part of the research for my book.

Initially, Frazier wouldn’t talk with me in Las Vegas because I was “Ali’s man.” But at an evening party after the second day of taping, Joe approached me. He’d been drinking. And the bile spewed out:

“I hated Ali. God might not like me talking that way, but it’s in my heart. First two fights, he tried to make me a white man. Then he tried to make me a nigger. How would you like it if your kids came home from school crying because everyone was calling their daddy a gorilla? God made us all the way we are. He made us the way we talk and look. And the way I feel, I’d like to fight Ali-Clay-whatever-his-name-is again tomorrow. I still want to take him apart, piece by piece, and send him back to Jesus.”

Joe saw that I was writing down every word. This was a message he wanted the world to hear.

“I didn’t ask no favors of him, and he didn’t ask none of me. He shook me in Manila; he won. But I sent him home worse than he came. Look at him now. He’s damaged goods. I know it; you know it. Everyone knows it; they just don’t want to say. He was always making fun of me. I’m the dummy; I’m the one getting hit in the head. Tell me now; him or me, which one talks worse now? He can’t talk no more, and he still tries to make noise. He still wants you to think he’s the greatest, and he ain’t. I don’t care how the world looks at him. I see him different, and I know him better than anyone. Manila really don’t matter no more. He’s finished, and I’m still here.”

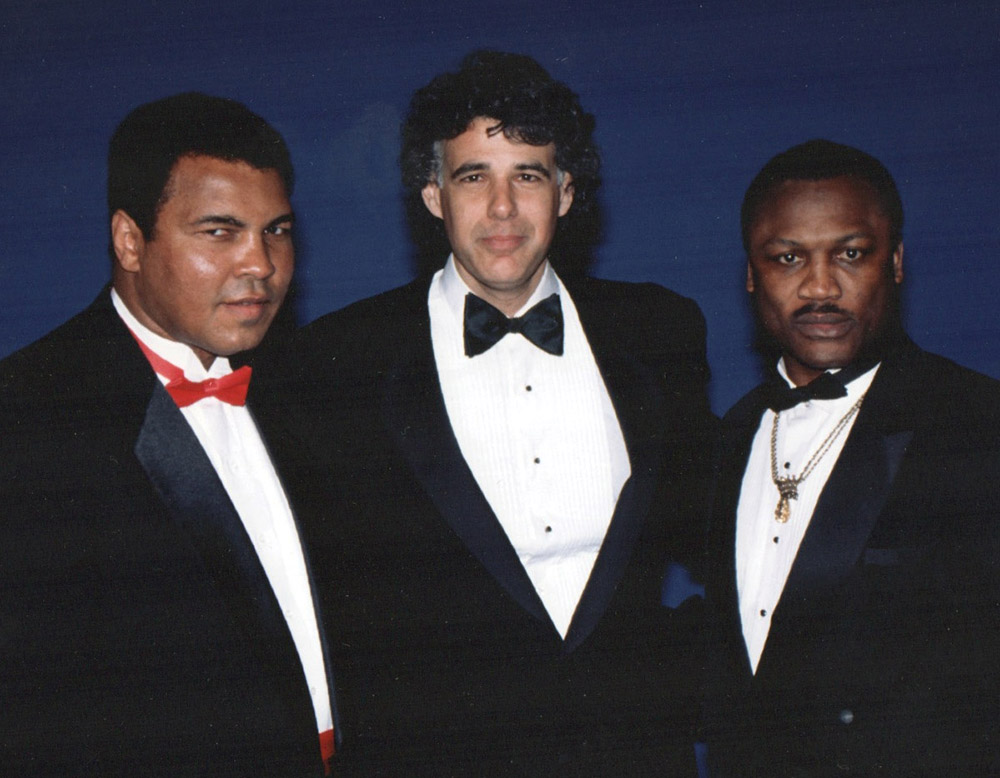

There’s a painful secret lurking behind this seemingly innocent group photo of Ali, Frazier and author Thomas Hauser.

April 14, 1991, in Philadelphia was to be Frazier’s night. After all, Joe had won Ali-Frazier I. But 20 years after that fight, his hatred for all things Ali remained palpable. Now, during the cocktail hour, Howard suggested that I pose for a photo with Muhammad and Joe. I stood between them. Joe wrapped his arm around my waist in what I thought was a gesture of friendship. Then, just as Howard snapped the photo, Joe dug his fingers into the flesh beneath my ribs.

It hurt like hell.

I tried to pry his hand away.

You try prying Joe Frazier’s hand away.

When Joe was satisfied that he’d inflicted sufficient pain, he smirked at me and walked off.

Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times was published in June 1991. Someone read Joe the parts in the book that were about him, and he decided that I’d treated him fairly. In the years that followed, when our paths crossed, he was warm and friendly. A ritual greeting evolved between us.

Joe would smile and say, “Hey! How’s my Jewish friend?”

I’d smile and say, “Hey! How’s my Baptist friend?”

That led to the afternoon of January 7, 2005. Joe was in my home. We were eating ice cream in the kitchen.

Then Joe said something that surprised me.

“Do you remember that time I gave you the claw?”

“I remember,” I said grimly.

“I’m sorry, man. I apologize.”

That was Joe Frazier. He remembered every hurt that anyone ever inflicted upon him. With regard to Ali, he carried those hurts like broken glass in his stomach for his entire life. But Joe also remembered the hurts he’d inflicted on other people. And if he felt he’d done wrong, given time he would try to right the situation.

As for Ali . . . Talking about Joe, Muhammad told me, “I’m sorry Joe Frazier is mad at me. I’m sorry I hurt him. Joe Frazier is a good man. I couldn’t have done what I did without him, and he couldn’t have done what he did without me. And if God ever calls me to a holy war, I want Joe Frazier fighting beside me.”

Thomas Hauser’s email address is [email protected]. His most recent book – A Dangerous Journey: Another Year Inside Boxing – was published by the University of Arkansas Press. In 2004, the Boxing Writers Association of America honored him with the Nat Fleischer Award for career excellence in boxing journalism. Hauser will be inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame with the Class of 2020.