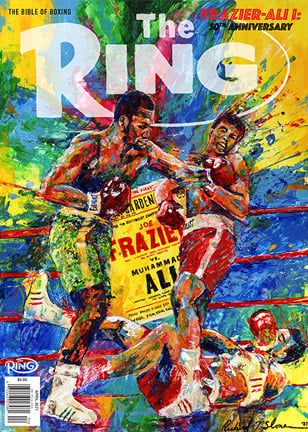

LONG BEFORE THEY MET AT THE CROSSROADS IN 1971, ALI AND FRAZIER STARTED THEIR PRO JOURNEYS AS OLYMPIC CHAMPIONS

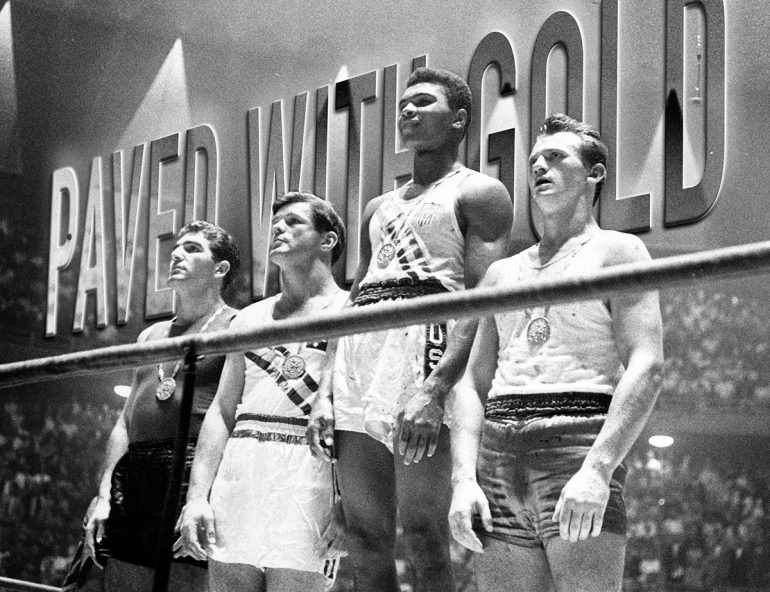

“If someone had told me back then that Cassius Clay would become the most famous person in the world, I never would have believed them,” Skeeter McClure said as he remembered how he had been Muhammad Ali’s roommate at the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome. “It just didn’t seem possible.” McClure, who died in 2020, won Olympic gold for the U.S. as a light middleweight. Thirty years later, when he was a psychotherapist and business executive, he shared memories of his old teammate in Thomas Hauser’s magisterial Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times.

Cassius Clay, as Ali was known then, was already a big talker who became the Olympic light heavyweight champion in Rome. But McClure was struck most by the 18-year-old Clay’s shyness when not proclaiming his own extraordinary ability as a boxer. He was amused that, at an amateur tournament in Chicago, Clay “kept bugging everybody on the team, saying, ‘Man, there are all these pretty girls walking around. We got to meet some of these girls.’… Then we went into the cafeteria, which was filled with more pretty girls. And the guy who had been agitating just sat there, staring at the food on his tray the whole time. He didn’t say a word. We teased him about it for days, and all he did was look at us and shrug his shoulders. He was very, very shy around girls.”

Joe Frazier was another shy young man. Even after he equaled Clay’s achievement by becoming an Olympic gold medalist in October 1964, Frazier remained reserved. Mark Kram Jr., who wrote the definitive biography of Smokin’ Joe, describes Frazier’s return from Olympic glory: “Only 20, he carried himself in public with an agreeable humility that Stan Hochman characterized in the Philadelphia Daily News as ‘doorman-like politeness.’” The idea that Frazier might become inextricably linked to the most exalted athlete in the history of sports would have also seemed absurd then.

Yet, six-and-a-half years later, Ali and Frazier would meet for the first time in the Fight of the Century at Madison Square Garden. They were both unbeaten Olympic champions who had traveled very different roads to reach that tumultuous point. The political, personal and boxing pathways followed by each man have been documented exhaustively – but their respective Olympic journeys are less familiar.

A gold medal was the first real token of the glory and the adulation that would define the world’s reaction to Ali in later decades.

Their Olympic experiences contain the foundations of their boxing lives as well as the similarities and contrasts that define their unique rivalry. Yet both Ali and Frazier came close to missing out on the Olympics completely.

By 1960, Clay had fought 108 amateur bouts while winning six Kentucky Golden Gloves titles, two national Golden Gloves tournaments and two National AAU championships. His boxing credentials were excellent, but his shyness outside the ring was matched by a terror of flying. “We had a rough flight going to California for the [Olympic] trials,” recalled Joe Martin, his amateur trainer. “So when it was time to go to Rome, he said he wasn’t gonna fly and that he wouldn’t go. I said, ‘Well, you’ll lose the opportunity of being a great fighter,’ and he said, ‘Well, I’m not gonna go.’”

Four years later, Frazier also seemed fated to miss out on the Olympics. He was devastated to lose a controversial decision to Buster Mathis in the heavyweight final of the U.S. trials. Before the fight, Mathis was considered the favorite because of his extreme size and the fact he was deceptively light on his feet and had quick hands. He was a little like a 1960s version of Andy Ruiz Jr., another chubby man who dismantled an Olympic gold medalist in Anthony Joshua in the summer of 2019, but Mathis was even larger. Before he went into training for the trials, the 6-foot-3 Mathis weighed 340 pounds and Robert H. Boyle was scathing in Sports Illustrated: “Sitting in his corner, he looks like a melting chocolate sundae.” But few boxing experts believed a relatively small heavyweight such as the 5-foot-10 Frazier, who weighed 196 pounds, could keep the gigantic Mathis at bay.

Four years later, Frazier also seemed fated to miss out on the Olympics. He was devastated to lose a controversial decision to Buster Mathis in the heavyweight final of the U.S. trials. Before the fight, Mathis was considered the favorite because of his extreme size and the fact he was deceptively light on his feet and had quick hands. He was a little like a 1960s version of Andy Ruiz Jr., another chubby man who dismantled an Olympic gold medalist in Anthony Joshua in the summer of 2019, but Mathis was even larger. Before he went into training for the trials, the 6-foot-3 Mathis weighed 340 pounds and Robert H. Boyle was scathing in Sports Illustrated: “Sitting in his corner, he looks like a melting chocolate sundae.” But few boxing experts believed a relatively small heavyweight such as the 5-foot-10 Frazier, who weighed 196 pounds, could keep the gigantic Mathis at bay.

Frazier believed in himself. He also sent Mathis a warning in the trials by knocking out the AAU champion, Wyce Westbrook. Clay Hodges was another crumpled victim after he was stopped by Frazier in Round 2 of the semifinals.

Frazier was convinced he could beat Mathis. “My only problem,” he predicted, “will be getting out of the way when he falls.”

The heavyweight final of the 1964 Olympic trials was a complicated affair. Mathis had been troubled so badly by high blood pressure, caused by his excessive weight, that doctors instructed him to lie down all afternoon before they allowed him to fight. His slumbering rest seemed to help, for once the opening bell rang, Frazier’s brutal punching did not seem to bother Mathis much. The big man glided away from most of the punches with surprising alacrity, and even when Frazier landed, Mathis seemed unfazed.

Frazier was not helped when two points were deducted for low blows, but most reporters were certain he had done more than enough to clinch his place on the Olympic team. When the decision was announced in favor of Mathis, Dave Anderson wrote: “They seemed to be dazzled by his ballet, instead of his punches. I wondered if we were watching the same fight.”

The result seemed so wrong that Frazier promised to quit boxing. He would go back to Philly and forget all about the Olympics and the pro game. In Kram’s book, a touching scene is described. “Frazier spotted Philadelphia Bulletin boxing writer Jack Friend, who had been attentive to his amateur career. Joe shook hands with him and said: ‘Thanks, Jack, for all you did for me.’ Anderson remembered thinking: ‘This is a guy with some heart.’”

Four years earlier, Clay had also displayed his heart in the final of his Olympic light heavyweight trial. After easy victories in the earlier rounds, he faced an imposing rival in Allen “Junebug” Hudson, a former soldier who had knocked out his semifinal opponent in 32 seconds. Clay might have been shy and scared of flying after his bumpy arrival in San Francisco for the nearby trials, but he knew he could whip every amateur fighter he faced. He won the first two rounds in the final, moving with the slick fluidity that would define his greatest years in the ring, before a left hook dropped him.

Clay would come of age in his TKO 7 win over Sonny Liston in Miami Beach.

But the resilience that would also distinguish Ali when he became a world champion was already obvious. The Louisville teenager got up immediately with gritty defiance. Clay danced out of the way of some wild punches before, with clinical authority, nailing Hudson with a heavy right hand. Another followed, and Hudson went down. He could not match the toughness of Clay and, on jittery legs, Hudson was rescued by the referee.

Cassius Clay had won the right to fight in the Rome Olympics. The drama, however, had just begun. After Clay failed to persuade Martin to loan him the money to catch a train back to Louisville, rather than take the return flight, his anxiety deepened. He sold the gold watch he had won in San Francisco and used the cash for a rail ticket back to Kentucky.

His long train journey home hardened his resolve, and he made his impassioned speech to Martin about not flying to Rome. Martin told Hauser it took almost three hours for him to calm down Clay in Central Park in Louisville. “I convinced him that if he wanted to be heavyweight champion of the world, he had to go to Rome and win the Olympics.”

Frazier, in contrast, was despondent four years later when it seemed as if his chances of fighting at the Tokyo Olympics had been ruined. He was also near destitute, and when he was asked to travel to San Francisco as a substitute covering the heavyweight and light heavyweight selections, Frazier did not think he could afford it. He worried about losing his low-paid job as a butcher in Philadelphia, and even when reassured that he would not be fired, Frazier struggled to pay for his trip.

Frazier, in contrast, was despondent four years later when it seemed as if his chances of fighting at the Tokyo Olympics had been ruined. He was also near destitute, and when he was asked to travel to San Francisco as a substitute covering the heavyweight and light heavyweight selections, Frazier did not think he could afford it. He worried about losing his low-paid job as a butcher in Philadelphia, and even when reassured that he would not be fired, Frazier struggled to pay for his trip.

Three weeks before the start of the Tokyo Olympics, Frazier and Mathis fought an exhibition bout at an Air Force base. It followed the same pattern as their fight in the Olympic trials. Frazier landed the meaningful punches, but Mathis was awarded a contentious decision. But the fighting gods had seen enough. Mathis had broken a knuckle on his right hand and would not be able to fight in the Olympics.

When Frazier took the call asking him to step in as Mathis’ replacement, he cried out: “Oh, God! Thank you, God!”

Four years earlier, Clay survived the flight to Rome. He distracted himself by chatting incessantly to his teammates. The American press corps was downbeat about any gold medal prospects for their boxers. Such pessimism did not affect Clay, who predicted that both he and his old pal Skeeter McClure were certain to win gold. His wide-eyed enthusiasm and garrulous nature blossomed once he was in Rome. He was described by a reporter as being “as friendly and frisky as a puppy” as he used his small camera to take photographs of his first visit abroad. “Took 48 pictures today,” he told the reporter before handing over his camera so that he could join a group shot with a bemused group of fellow tourists.

Clay’s shyness also faded as he flirted with Wilma Rudolph, the great American sprinter who would win three gold medals in Rome, and gazed longingly at other beautiful young female athletes from around the world. His outrageous charisma was already obvious, and even the stars gravitated towards Clay. He met Bing Crosby in Rome, and he and the old crooner strutted arm-in-arm for the cameras. Floyd Patterson, an even shier man who had regained his world heavyweight title a few months earlier, was introduced to Clay. He was still only an amateur, but Clay pointed out that he was taller and had a longer reach than the world champion. “Be seeing you in about two more years,” Clay warned Patterson.

McClure saw the drive in him. “In Rome, he was outgoing,” McClure said of Clay, “but he was seriously into boxing. I don’t know of anybody on any team who took it more seriously than he did.”

Clay knew he was fighting in a fiercely competitive division. There were many medal contenders, but Zbigniew Pietrzykowski was the overwhelming favorite. The Pole had been European champion on three occasions and won bronze at the 1956 Olympics (at light middleweight) in Melbourne. He was 25, in his prime, and had fought over 200 bouts. Clay claimed to be unimpressed – describing Pietrzykowski as “some guy with 15 letters in his name.”

The tournament began well for Clay. He knocked out Yvon Becot from Belgium and dazzled and pummeled Gennadiy Shatkov, a Russian who had won Olympic gold in Melbourne four years before as a middleweight. The semifinal was more testing, but Clay was still far too skilled for Tony Madigan, a rugged Australian. The teenager from Louisville was in the Olympic final against the experienced Pietrzykowski.

via joshmar11 on YouTube:

Clay was more circumspect in the opening two rounds against the Pole, who fought out of an awkward southpaw stance. The American looked to have shaded them, but a big last round for Pietrzykowski could’ve still tilted the balance. Clay shut down any doubts with an imperious flurry of punches that made blood spurt from Pietrzykowski’s nose and mouth. His shimmering brilliance had transformed a hardened European champion into a hapless amateur who, as William Nack wrote later in Sports Illustrated, suddenly resembled “a portly coffeehouse keeper from Poland.” Pietrzykowski’s vest was covered in blood, which also turned Clay’s white trunks a pale shade of pink. The final bell offered merciful relief to Pietrzykowski.

An Olympic gold medal was soon draped around Clay’s neck. It was the first real token of the glory and the adulation that would define the world’s reaction to Ali in later decades. Of course, in changing his name while embracing the Nation of Islam doctrine and standing up to racism in America, Ali would also face resentment, anger and a three-and-a-half-year ban from boxing before he fought Frazier in March 1971.

His great rival also encountered adversity and misunderstanding. Frazier was only two years older than Clay had been in Rome, but he was a more mature man who understood his responsibilities. Every day in Tokyo, he wrote to his wife, Florence, telling her how much he loved her and their three children and that he would win the gold medal.

After a first-round stoppage win over Uganda’s George Oywello, Frazier was dropped by Athol McQueen, the Australian, early in their quarterfinal. It was the first time Frazier had been knocked down, and he responded with characteristic fire. He dominated the rest of the fight and stopped McQueen in the final round. Frazier was also staggered early in his semifinal by Vadim Yemelyanov, but he again responded magnificently to stop the Russian and secure his place in the final.

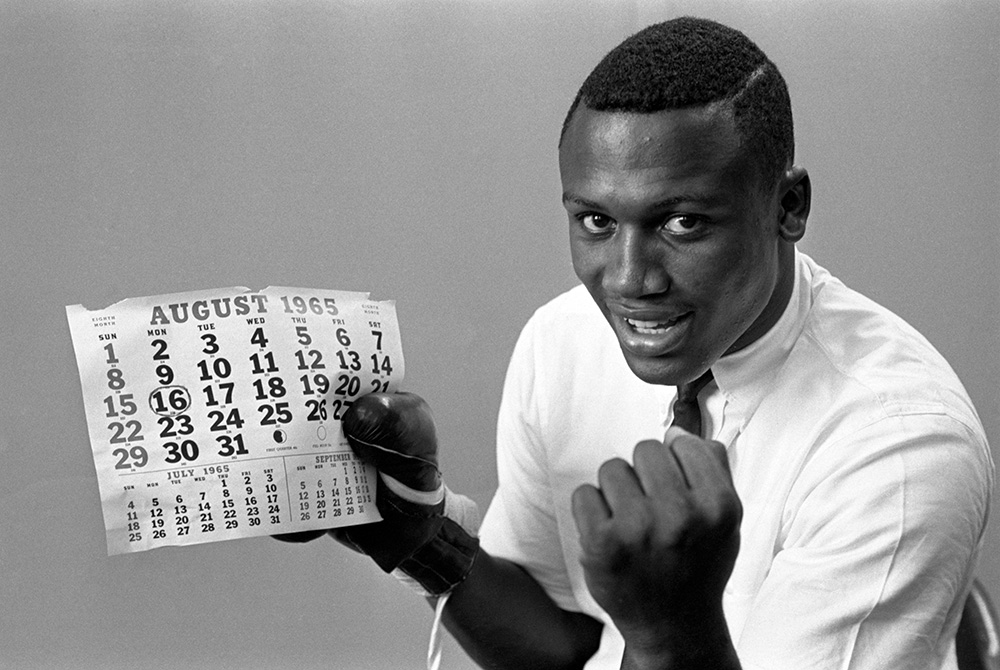

Frazier would earn partial recognition as champ at the expense of Buster Mathis. (Photo by Ralph Morse/Life Magazine/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images)

The real toughness of Smokin’ Joe only emerged later. He had broken his left thumb against Yemelyanov, but he refused an x-ray because he was worried he would be forced to withdraw from the final against the German Hans Huber. Even with a busted hand, the gulf between the two fighters was vast, and the only surprise was that two of the judges chose Huber as the winner. But three judges correctly identified Joe Frazier as the Olympic heavyweight champion.

Unlike Clay, who was soon contracted to a Louisville consortium, Frazier did not receive any immediate offers to turn pro. Kram stresses that Frazier’s prospects appeared limited and he “found himself in a state of limbo.” Whereas 10 of the 11 white men in the Louisville Sponsoring Group were millionaires or members of extremely wealthy Kentucky families, it was different for Frazier. He was broke and jobless after he could not return to work at the butchery in Philadelphia. Instead, he had to endure two operations on his fractured thumb.

Joe Frazier would not be denied either. But he was forced to take a longer and harder road.

Frazier was worried, but he retained his sense of decency. Kram writes that, four days before Christmas in 1964, Frazier spoke for an hour to eighth-grade students. Their teacher, W.P. Moran, wrote an appreciative letter to the Philadelphia Inquirer: “He was delightful. The children loved him. He was good for them. … There should be more Joe Fraziers in the world.”

There could be only one Muhammad Ali. Earlier that year, in February 1964, he had shocked the world by knocking out the fearsome Sonny Liston to become heavyweight champion of the world. His Olympic achievements had set him on this path but, as so often happened with Ali, a myth eventually enveloped his gold medal. It was claimed wrongly in his 1975 autobiography that, in protest against America’s racism, he had flung his Olympic medal in the river soon after his return home. The truth was more prosaic. He was seen holding his medal as late as 1963, and Ali admitted at a press conference after the book was published that he had merely lost the medal. The heavyweight champion of the world did not need a shiny piece of metal to remind him that his path to boxing glory had begun in Rome.

A 21-year-old Joe Frazier marks the date of his pro debut.

Joe Frazier would not be denied either. But he was forced to take a longer and harder road. In 1965, Frazier made a living by lugging crates in and out of a removal van. It was not work befitting the Olympic heavyweight champion. He was desperate for promotional backing but, without it, Frazier made his pro debut at the Convention Hall in Philadelphia against Woody Goss in August 1965. After 102 seconds, referee Zack Clayton stopped the fight because, in his words, he wanted “to keep Goss from getting killed.”

Frazier’s first four fights were all won easily but, by the end of 1965, 14 months after he had won gold in Tokyo, he was still without any backing. It took Billy Gray, a pastor who had given Frazier additional work as a janitor at his church, to galvanize a consortium of white business leaders in Philadelphia to set up a group called Cloverlay. Influenced by the success of Ali’s Louisville Sponsoring Group, the more modestly funded Cloverlay consisted of 40 investors who paid $250 each for an initial 80 shares in the backing of Joe Frazier. The fighter himself called it “a swell deal” because it guaranteed him a weekly salary of $100 and 55 percent of each purse, rising to 60 percent if he and the Cloverlay group extended their option.

Frazier made his debut as a Cloverlay fighter on January 17, 1966. He felt like a proper professional fighter at last and, full of fresh hope, he knocked out Mel Turnbow in the first round. Smokin’ Joe, with a 5-0 record, was on the rise. He fixed his gaze on a fellow Olympic champion.

Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier, the kings of Rome and Tokyo, were on a collision course to immortality.